What follows is a review/discussion by three diverse authors…all enthusiastic creators and readers of pulp adventure. The three of us met in 2021 and immediately enjoyed one another’s company and writings to the degree that we joined in the tradition of author circles like the 1930’s Kalem Club (a literary group whose last names all began with K, L or M, and included H.P. Lovecraft) and the Inklings, the Oxford circle made up of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and Charles Williams. A brief introduction: Atom Mudman Bezecny is both an author and publisher, and created the Hero Saga, which has brought to life unique pastiches of classic — and some wonderfully obscure — pulp characters. R. Paul Sardanas is the co-creator (with artist Iason Ragnar Bellerophon) of the Doc Savage adult pastiche Talos Chronicle, and André Vathier is a French Canadian author who has written stories in both the Hero and Talos “universes”. Together we comprise the Conseil du Mal (or Council of Evil)…dedicated to wicked literary pleasures of all kinds!

SARDANAS: Hi Atom, Hi André, good to have the Conseil du Mal assembled again to discuss another book that’s been influential to modern pulp writing. We’re going to talk today about Harold Bloom’s The Flight to Lucifer, an intriguing choice for a modern pulp conversation, as it was first published in 1979, with an unusual literary provenance behind it, and perhaps equally unexpected influences on pulp writing ahead of it. Bloom has made his formidable reputation as a literary critic, most famously producing many books discussing the works of William Shakespeare. But one of his own favorite books was a bizarre pulp-visionary 1920 novel by David Lindsay, called A Voyage to Arcturus. Here’s a description of the book and some of the luminaries it inspired:

A Voyage to Arcturus is a novel by the Scottish writer David Lindsay, first published in 1920. An interstellar voyage is the framework for a narrative of a journey through fantastic landscapes. The story is set at Tormance, an imaginary planet orbiting Arcturus, which in the novel (but not in reality) is a double star system, consisting of the stars Branchspell and Alppain. The lands through which the characters travel represent philosophical systems or states of mind as the main character, Maskull, searches for the meaning of life. The book combines fantasy, philosophy, and science fiction in an exploration of the nature of good and evil and their relationship with existence. Described by critic, novelist, and philosopher Colin Wilson as the “greatest novel of the twentieth century”, it was a central influence on C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy, and through him on J.R.R. Tolkien, who said he read the book “with avidity”. Clive Barker called it “a masterpiece” and “an extraordinary work … quite magnificent”.The book sold poorly during Lindsay’s lifetime, but was republished in 1946 and many times thereafter. It has been translated into at least ten languages. Critics such as the novelist Michael Moorcock noted that the book is unusual, but that it has been highly influential with its qualities of “commitment to the Absolute” and “God-questioning genius”.

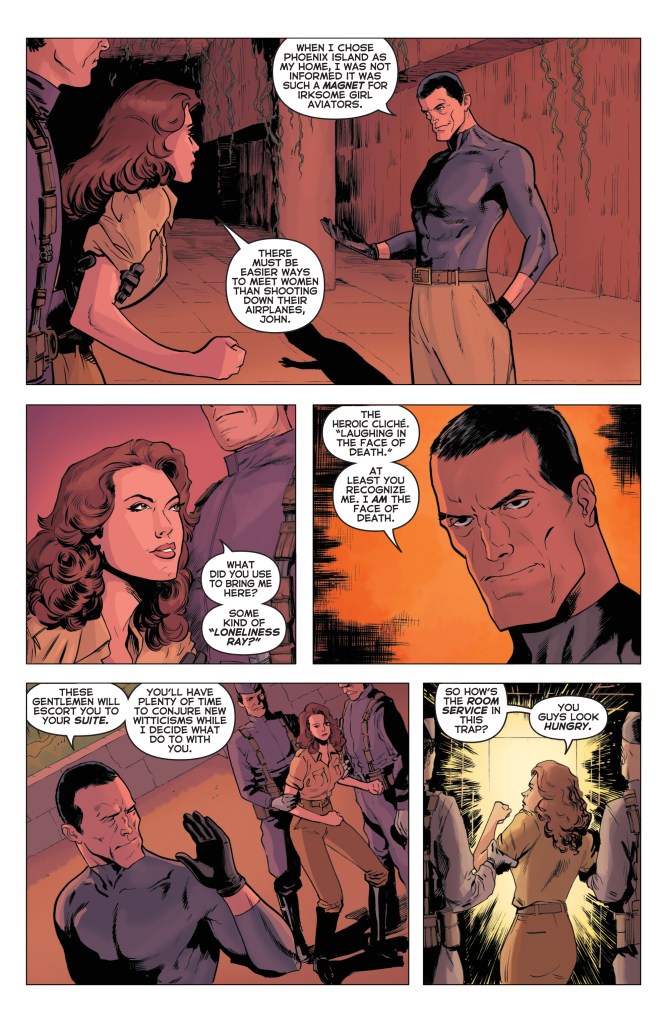

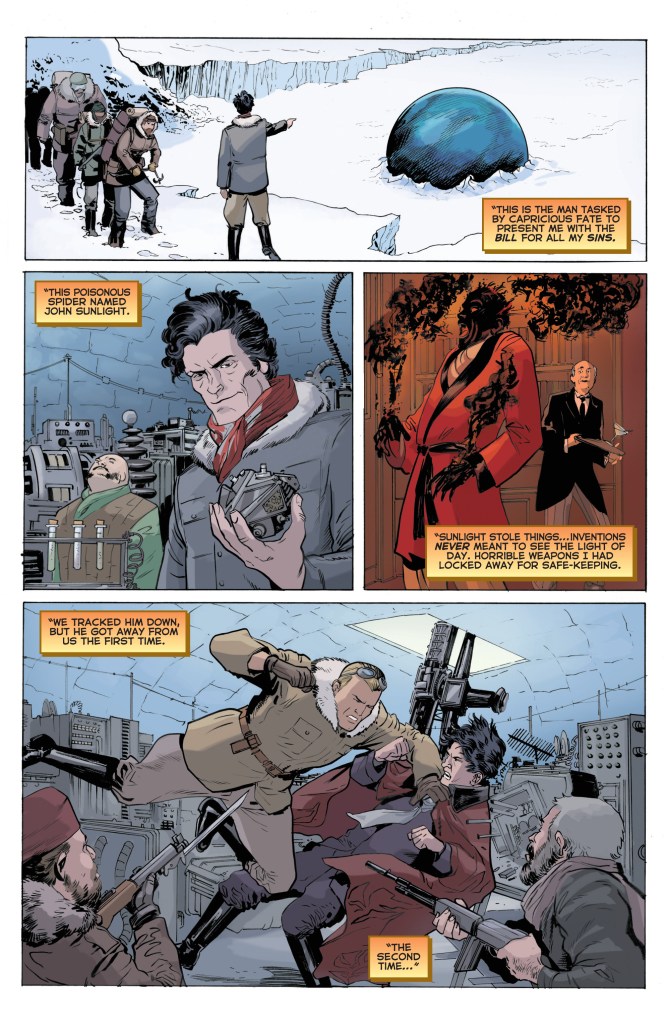

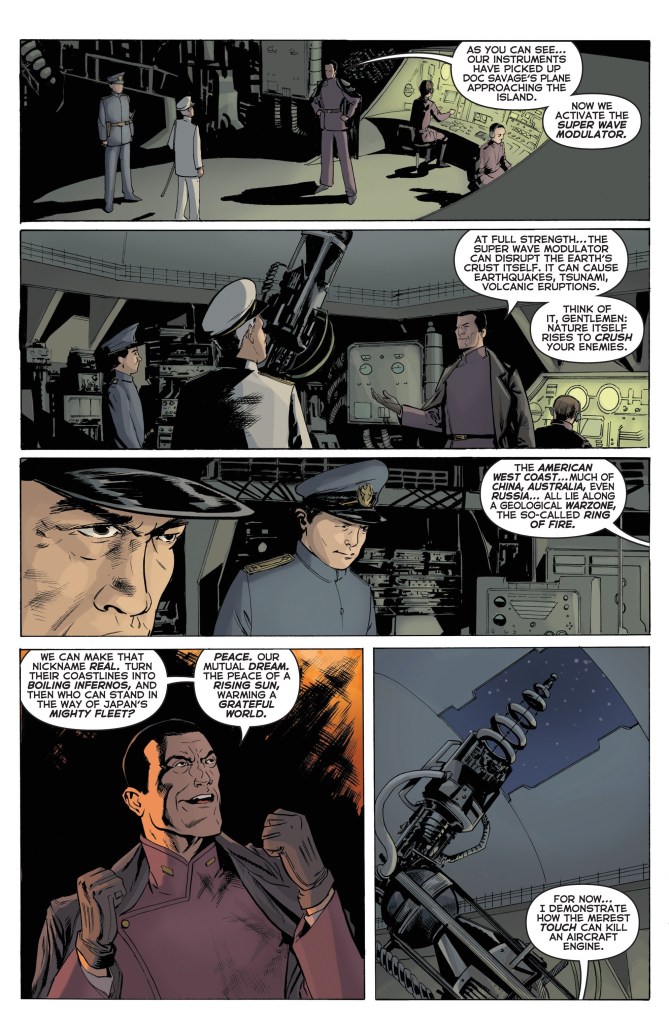

A very incongruous collection of admirers…some from the literary ivory tower, others from the horror and adventure-fantasy genres. And the book itself is written in a style that is often blunt and unconstrained, practically the opposite of a “high literary” narrative. It reads, in fact, like a pulp novel. Bloom’s admiration for the book led him to write the only novel of his long career, The Flight to Lucifer, which re-imagines A Voyage to Arcturus in terms of Gnostic belief. Bloom somewhat notoriously hated his own creation – once saying that he wished he could buy back every copy printed and burn them all (the fate, ironically, of many an old pulp magazine and comic book in the hands of parents who considered them “trash”). The Flight to Lucifer also did not sell well, and was savaged by many critics…most commonly objecting to its dry scriptural tone, mixed with bursts of violence and dark eroticism more commonly to be found in pulp lit. In fact some of its scenes are strongly reminiscent of Philip José Farmer’s pulp-pornographic novel A Feast Unknown. Four decades later, The Flight to Lucifer would also provide a layer of inspiration to myself and artist/co-creator Iason Ragnar Bellerophon in our creation of the Doc Savage pastiche Doc Talos, and the six-volume Talos Chronicle. In A Voyage to Arcturus, and in some ways even more strongly in The Flight to Lucifer, is a fascinating blueprint for both the elevation of pulp fiction – or equally true, the infusion of visceral elements from those same “bloody pulps” into the dry and scholarly realm of literary fiction. A trip upward toward the ivory tower, while at the same time improbably tearing down that tower and hauling its pretensions (kicking and screaming) down into the mass readership of the pulp world.

BEZECNY: That’s a pretty apt description, as both Lindsay and Bloom’s books involve characters ascending physical towers which are actually more like dimensional bridges, warping them across infinity to the respective titular planets. Both stories are, fundamentally, about the passage from the material world into a spiritual world of gnosis, and this early sequence literalizes that. It really is interesting to me, the balance that Bloom strikes between pulpy and literary aspirations. On one hand, his book is an intellectual academian recontextualization of an earlier fantasy story. On the other, the book has a curious obviousness to it if one has already read Voyage to Arcturus. Bloom is very much telling the same story as Lindsay, down to the same sequence of events, but in a way that makes Lindsay’s incidental Gnosticism much more clear. It’s a smart criticism because it takes a strong knowledge of religious and mythic themes to come up with such a direct correspondence. But in changing the names of Lindsay’s places and characters into Gnostic variants, Bloom is crafting a surprisingly simple narrative, and in some ways he is stripping some of the magic out of Arcturus in a way that feels almost materialistic. And yet the revelations about Lindsay’s work which Bloom draws are almost Gnostic in their transformative nature. He creates the sort of paradox which my weird spiritual beliefs associate with the godly. This is essentially the same as rewriting the Narnia books to replace Aslan’s name with Jesus, but the simple fact that David Lindsay didn’t intend for his book to serve as a Gnostic vision makes this case a very different animal (pun intended?). The issue with good pastiche is that it wouldn’t exist without its predecessor. At the same time, criticism is, in an ideal sense anyway, about progress. It’s about investigating the old to inspire the new. Good criticism opens up new views of old stories that make them shine brighter (or stranger) in new light. And sometimes that fresh illumination comes from a crossing of the supposed barriers separating “highbrow” from “lowbrow.” Like A Feast Unknown, this book melds those two barriers together to shine light on both attributes at once. It can’t be contained by conventional criticism and yet in that sense it is in some ways participating in the ultimate form of criticism.

VATHIER: See I think I made a mistake by not reading A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay first. I decided to jump right in. It is sort of becoming a tradition whenever I talk to both of you. I missed the subtleties of the book. Because I have not read the previous, work it pastiches. We should start a drinking game. Take a shot whenever André tells you he has not read a work or is unfamiliar with an English-language author. I must admit, I found it to be a frustrating read at first. I was not enjoying it. Parts of the book reference previous works or concepts that i felt I should get but I did not. Therefore, after a while I decided to start over and just “feel” the book instead of understanding it through the lens of a pastiche or academic highbrow. Reading it that way was more enjoyable. Bloom’s style is interesting. He’s an academic. I thought it would be Umberto Eco type book.Where he flexes his academic knowledge. However, the small chapters in The Flight to Lucifer are perfectly made to convey emotions. That is what I like about it. Like A Feast Unknown this book is emotionally intense. It’s raw in a way that very few authors dare to go. After I was done with it, I decided to read some of the Goodreads reviews. It’s either “This book is great” or ‘’This book is the worst book I ever read in my entire life”. There very little in between. I feel a lot of the critics miss the forest for the trees. This is unrelated but the Wikipedia states the following. “The book received negative responses, and was compared, including by Bloom himself, to the film Star Wars (1977)” Star Wars? Personally, I do not see it.

SARDANAS: In a way André, the fact that you read The Flight to Lucifer without first reading Lindsay’s book gave you a unique perspective — sometimes the experience of pastiche-first, original-second can be very illuminating. Particularly since Bloom’s style is distinctly academic, and Lindsay’s is almost anti-academic. Interesting point Atom, that Bloom, as a lifelong literary critic, actually achieved a unique form of criticism through his only novel as well. As you know I’m fascinated by both the dichotomy and potential symbiosis in “highbrow” and “lowbrow” literature, and while Bloom himself (by disowning his own book) disliked the result, he did indeed take Lindsay’s often amateur-like writing (Lindsay did things like make up words instead of finding sophisticated ways to describe unique elements of the story…in addition to a sometimes crude and simplistic style) and shape it with a much more disciplined hand. Interesting too that we all feel an analogue to aspects of Farmer’s raw, intense A Feast Unknown in The Flight to Lucifer. I agree with you André, Bloom took the narrative at times to places many authors are too timid (or too limited) to explore…as did Farmer. How all this relates to modern pulp writing comes into play in intriguing ways. In the modern pulp-author community, I see a lot of frustration among authors who feel “no one is listening”. Low sales, lack of widespread fame…of course those can be discouraging, but I feel that sometimes those frustrations will lead to modern pulp authors abandoning faith in their own most innovative and challenging concepts. If the criteria for achievement is sales and fame, both Lindsay and Bloom as novelists were resounding failures. Lindsay, discouraged after Arcturus’ poor showing commercially, shifted gears and attempted to tailor his next works to commercial tastes, resulting in books that have been utterly forgotten. Bloom returned to his critical writings (for which he has wide readership and acclaim)…but Lucifer arguably continues to inspire as much as any of those works over forty years after its publication. Both books have achieved what might be thought of as “underground” followings. People are passionate about them (as you say André, often either strongly loving or hating) which I actually consider a hallmark of important books. Perhaps at least part of the lesson to today’s writers being faith that a willingness to go out on a limb to present a powerful personal vision may not make you a cartload of money, but may inspire passion in readers a half or full century after you write those works. Pulp readers have a strong affinity — and deep loyalty — toward characters and authors that strike a deep chord of emotion, often defying commercial convention while they are doing it.

BEZECNY: If it’s any comfort, André, I tend to read pastiches way before I read the originals. I’ve read far more Doc Savage pastiches than I have original novels. I think these two books have a dualism that lets you indulge them in either order. I agree with you that Lucifer doesn’t quite work as a pure sequence of events; it’s more like prose poetry, and viewed through that lens it’s very effective. Alas, no one really likes prose poetry, probably because they’ve only read bad examples, when in fact there are many, many good examples out there. Critics, in an effort to sell to increasingly narrow algorithms, have to display more and more intensely polarized opinions, which means that books like this are never very popular. Capitalism and art just don’t mix. I think that’s partly why the Star Wars comparison came up–even in the 80s, there was a push to always compare lesser known stories to better known ones, because marketing. There was a time not too long ago when every single new sci-fi book that came out was said to be “just like Stranger Things” when it had nothing in common with that show. I think it’s hard because the same environment and social system which has led to this lack of mainstream critical nuance is also that which is starving most of the world’s population. The disparity between wages and costs of living is growing worse without anyone in power seemingly interested in halting it. No one wants to work a job that kills them on an emotional level, and so making a living wage in the creative arts involves serving the creative wishes of corporations. This isn’t to say that every author who’s made it is a sellout–far from it. But there are creators whose visions are inherently going to be held back from success because they run contrary to the acceptable conservative status quo. And it’s very easy to see that many people view the exercise of imagination or the creation of “high art” as a symbol of privilege. But I don’t think any of that reduces the necessity of the sort of creativity that authors like Lindsay and Bloom put forward. I think that it’s important to challenge boundaries and meld mutual exclusitivies even if those experiments aren’t always successful. As a lover of trash movies, I know that there’s always someone out there who will find value in a work which most condemn as useless.

VATHIER: Atom You talk about your love of trash movies. Youtuber Kyle Kallgren said the following in one of his videos. I think it applies really well to the book too. “Even a badly worded statement can inspire. Even a poorly made gesture can move “ It’s sad that Harold Bloom never tried fiction ever again. He of all people should know that practice makes perfect. Commercial failure does not mean failure. Consequently, I have noticed it to Paul. That frustration among pulp author is about “no one is listening low sales, lack of widespread fame”. I do not share that frustration. On the other hand, I do not have that need for that widespread fame. I mean knowing that both of you read and enjoyed my short stories filled me with Joy. I share your opinion. If authors cannot make a living from writing then they totally should write a book or produce a piece of art that is personal or just follow their own vision regardless if it will be commercially successful. Atom you mention that capitalism and art do not mix. I agree I have seen authors; content creators online try to quantify or create “objective” parameter for judging and creating art. I dislike the fact that people online feel the need to justify what they like or what they find inspiring. What happened to liking something just because you do? Paul if it were not for you, I would never have picked up Flight to Lucifer. For one before you brought it up I had never heard of the book (I think Bloom himself is the cause of it .Allegedly paying the editor a large sum of money so it never gets a second printing or editions). I am curious to know where you first heard of it and when you first read it. Reading Flight to Lucifer after reading your Talos Chronicle stories. I could see it’s a source of inspiration for you.

SARDANAS: An interesting sidelight to the “trash film” side of the conversation – there is a terrific trash movie of A Voyage to Arcturus which was made in 1970 by student actors and filmmakers…done on a shoestring budget with almost no special effects, it is a fantastic example of a film being made on heart and inspiration alone. Extremely difficult to find, I snapped up a copy when it was briefly available on DVD, and was alternately appalled and enthralled by its crudity of technique melded to an intense dedication to filming “the book that is impossible to film”. No underground film fan should fail to see it sometime in their life.

Regarding art and capitalism, they are indeed uneasy bedfellows at best, bitter adversaries at worst. When you add in the social disdain frequently aimed at “trash lit” – pulp storytelling being a notable wicked stepchild of the literary world – things get even more intense…and interesting. This is certainly one reason why I find The Flight to Lucifer such a compelling milestone. As you’ve described, Atom, it often reads like a prose poem, but loaded with an almost insane mix of elements that are hallmarks of pulp excess. For modern pulp authors, I think one distinct trap they can fall into is failing what I call the “Cardboard/Cartoon” test. Much pulp fiction of the 20th century was rooted in shallow, bloodthirsty plots, or driven by gimmicky sensationalism. Great fun, but given the sheer quantity of the stuff, it can feel stale when recycled over and over. I’m the last person to look down on mindless fun (mindlessness can be a Gnostic experience in and of itself), but in heroic pulp fiction, it is all too easy to fall into the comfort zone of reading and writing stories of hollow men and women. Everyone of course has their own personal touchstones for what makes pulp fiction enjoyable and inspiring. But I have used two books for decades as a test for whether or not I have (unconsciously or not) fallen down a hole where I am no longer striving hard enough. Those books are Farmer’s A Feast Unknown and Bloom’s The Flight to Lucifer. Both books succeed and fail in some (actually in many) ways, but they show a courage in opposing the paradigm of cardboard characters in cartoon situations that is relentless. As both a reader and writer, I want to aspire toward that kind of courage. André to answer your question, I actually didn’t discover The Flight to Lucifer in what might be the expected manner – following the path from Arcturus (which I read in the 1970’s) to its pastiche, Lucifer. My mother was a Shakespeare and Blake scholar (my own name is a direct lift from a character in Macbeth), and by 1979 I was also heavily into both authors. This, of course, was Bloom’s wheelhouse…I was (and still am) endlessly fascinated by books like Bloom’s Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument, which I also read in the 1970’s. When I learned that Bloom’s first novel was going to appear in 1979, I acquired it immediately. Only on starting to read did I realize that this was a book with deep, deep roots in Lindsay’s Arcturus. I’ve always had one foot in the academic world and the other in the pulp world…and the synthesis of those in Lucifer practically had me hypnotized. When the time came, much later, to begin work on my own pastiche Talos Chronicle, I went back to those two mentor books, Feast and Lucifer, as core aspects of inspiration. Discovering that my creative partner for the Chronicle, Iason Bellerophon, equally treasured both books, was an incredible bit of serendipity.

BEZECNY: You can’t tell, dear readers, but I temporarily froze time in the middle of this conversation so that I could watch the Voyage to Arcturus film. It was an enlightening experience! Definitely a mixture of the exciting and the disappointing, as you said, R. It started off with a brilliant energy and then just sort of lost focus, presumably as deadlines and budgets ran out. But it did still capture a sliver of Lindsay’s novel. The dreamy cheapness of it was an adequate reflection of the almost incomprehensible pseudo-psychedelic atmosphere of that book. I wonder if Bloom ever saw the movie, either before or after he wrote Lucifer. I imagine that he and the filmmakers felt similarly about their respective products, but it’s a testament to the raw imagination of Lindsay’s work that it’s a hard thing to try to do twice. André, I love that quote by Kyle…it really defines my life and my perspective on things. Incidentally, I highly recommend pairing the Arcturus film with another student film from the ’70s, Moonchild from 1974, which managed to score both Victor Buono and John Carradine, two of my favorite actors. That movie, too, is overflowing with occult symbolism (including, as the title implies, Crowleyan themes) and was, I’m sure, an influence on the Eagles song “Hotel California.” We’ve talked now a little bit about the literary alchemy that Bloom’s practices, but I figure since this is kind of an obscure novel, and a complex one, it might be fun to dig a bit more into the plot. There are a lot of Gnostic names here, and modern readers can decipher much of the symbolism behind these names with the power of Wikipedia. But others, like Nekbael, are more elusive, and require some perusal of authentic Gnostic texts–those which survive, anyway. I’m curious what the two of you thought of the plot of this–and while I know you’ve both explored Gnosticism in your other writings, I’m curious to know how you reacted to this book’s spiritual themes on a personal level.

VATHIER: I will need to watch both movies now. Describing the plot can be difficult. The book does not have a traditional structure. Characters can fast-travel from one place to another in an instant. Multiple events happen concurrently. Some individuals that the characters meet along the way disappear without any explanation never to return. The plot summary from the Wikipedia article does not do the book justice. We follow Thomas Perscors with his friend Seth Valentinus an amnesiac who can remember a great deal and nothing at all and Olam a yellow-eyed being. Olam takes both men to the planet of Lucifer, Seth wants his memory back and Thomas Perscors’ purpose and quest are ambiguous for most of the story. You asked how I reacted to the spiritual theme on an emotional level. See while reading it. I quickly realized that I was not as well verse as I thought I was when it came the Gnosticism. Wikipedia did help but it only offered some superficial understanding. I will read this book more than once. I feel bad because I wish I could give more insight but to tell you the truth I did not fully understand the book. It frustrates me deeply because talking to you both of you obviously understood it. While I was left confused. This might because of my ignorance. (My knowledge of what Gnosticism is growing.) The fact that English is not my first language. However, I think the biggest reason above all else as to why I found this book to be a challenging read is this. I have not read A Voyage to Arcturus before reading this one. A lot of reviews call Flight to Lucifer a spiritual sequel or a re imagining of A Voyage to Arcturus and I am starting to believe them. I want to “get it” the same both of you “Get it”. However, I do not and it makes me frustrated, that led to slight anger. So seeing Thomas Perscors being angry in the book felt somewhat cathartic in a weird way because like him I was on an alien world that I did not fully understand.Speaking of Perscors. He reminds me a lot of a video game protagonist. I personally do not play video games but my partner and his friends do. Right now, they are playing a video game called Elden Ring. From what I can understand from watching them play, the game is set in a hostile fantasy world (Not unlike Lucifer) where your goal is complete quests while killing everything that stands between you and the quest. It’s kill or be killed. At one point, I asked my friends if a peaceful option was even possible. Like could they win the game by not killing a single character? They told me no. the mechanics would not allow it. To complete the quest you need to slash, hit, punch, kick, bite your way until the end. For those of you who know about the game I know there is a lot more to it than that but in that way Thomas was that video game protagonist. He listens to someone then moves forward killing or trying to kill anyone who stands in his path. Listen to someone else that makes the story go forward then he fights the person who crosses him, which segues into the next scene. In the book he’s a representation of Adam Kadmon (The primal man). Like a video game protagonist from a violent game both are an unstoppable force. I want to reiterate this is not a bad book. Confusing maybe. Nevertheless, its raw essence is very inspiring. It stays with you. It’s one of those pieces of art that relies a lot on what you bring to it.

SARDANAS: André, don’t feel troubled that your experience of the book was confusing. Part of that is due to not having experienced A Voyage to Arcturus, but that book is also mightily confusing. I have read both books multiple times for decades, and certainly make no claims to fully understanding them even now. And in a way, that is the point of a story that is at its heart a spiritual journey — in fact, multiple journeys. Like abstract art, I don’t believe its intent is for a full intellectual understanding. Instead, that kind of artistry can lead to feelings from a visceral place that no words can fully articulate. The story (sometimes literally) boosts a reader up to a platform where strange vistas can be viewed, but the viewing and the feelings provoked by that act are enough; to attempt prosaic explanations would drain those vistas of their majesty. Quite right Atom, we have explored a lot of oblique paths in talking about this story, but heaven forbid we should actually talk about the plot! André, you are also quite right, it is not a plot that can be easily summarized. In essence, a small group of individuals (Perscors, Valentinus, Olam) wander the planet Lucifer — mostly apart from one another — pursuing goals that are in no way clear. Perscors, though an intelligent and perceptive man, also embodies the Primal Man of Gnosticism, and frequently behaves in a distinctly primal manner. He flings himself into situations both sexual and violent. Valentinus is more deeply philosophical, but suffers from amnesia. His journey is one of slow and fragmentary remembrance of powerful beliefs that once made him a spiritual leader. Olam is a being from a higher existence (an Aeon in Gnostic language), and he is looking to reclaim a tower he once raised on Lucifer. He is coarse, blunt and powerful…but represents a form of unshakable honesty in a world filled with deceit and illusion. Each character runs a gamut of catastrophes, strange encounters with bizarre beings, and along the way there are numerous revelations that are tantalizingly opaque. By any measure, a strange story. But it is bold (as was Lindsay’s Arcturus) in its effort to create a visionary experience for the mind and soul. My personal responses — over decades now — are often ones of feeling that these characters are illustrating very important aspects of life, including my own life. That can feel exciting, frustrating…even frightening. It’s inviting readers to look at potentially very difficult aspects of being alive and human. Creatively, I have certainly found it inspiring. As mentioned previously, many aspects of the story provided pathways into human mysteries that I wished very much to explore…and did so (taking my own tangent on Bloom’s presentation of the Gnostic pantheon) in the Talos Chronicle.

BEZECNY: I also wanted to assure you, André, that this book is a hard read even among those of us for whom English is our first language. Like I said, it’s very much like prose poetry, and the feeling it evokes is in many ways more important than the story–but that’s not to say that those feelings are easy to conceptualize. The story itself is frustrating at times, because of how cryptic it can be and because oftentimes the characters act more in accordance to vague, unspoken mythic tropes rather than an ordinary sort of reason. In many ways this makes most if not all interpretations of the text valid. That’s part of why I enjoyed the book so much–but I am, as I’ve probably indicated many times here and elsewhere, fond of experimentalism for its own sake. There’s a lot of interesting intersections surrounding your video game interpretation. I do think it’s interesting how death and conquest are such important parts of games. It recalls Ronald Reagan’s statement that video games would create better jet pilots–there’s a certain militarism in giving kids stories which involve so much killing. A lot of popular, celebrated games are much smarter than this, but it is odd that young boys are expected to kill fictional characters as part of their upbringing. I feel inclined to target boys in this instance–sorry, gentlemen–because I have to admit that the conception of the Primal Man in Lucifer is often very patriarchal in his depiction. There is an emphasis on his Primal nature being tied to sex and murder, when in truth humanity’s Primal instincts are more complex than that. Our ancient ancestors learned to cuddle, to heal the sick, to feed each other, give gifts, etc. as part of their dawning sentience, and these too are part of our Primal ancestry. It’s been centuries of male-led anthropology that has convinced us that sex and death were the only instincts that mattered. We are compelled by so many different feelings that we take for granted. The video games that rise to the top, I feel, are the ones which incorporate these multiplicities into their experience, and don’t submit to status quo concessions. Much like any other medium. But I realize also that, while the Gnostics may have envisioned the Primal Man as our ancient ancestors, the concept of the Primal Man is one based on archetypes. In a sense, the Primal Man is a sort of cosmic everyman, a Platonic ideal of a spiritual traveler. In this, Perscors is much like the sort of allegorical protagonist found in books like The Pilgrim’s Progress. This in some ways makes Perscors’ violent tendencies more troubling. This is part of why “the West”‘s dependence on the imaginations of millennia-dead Europeans is an issue. The ancient stories, the myths of old, are very violent and very patriarchal. In replicating that vibe, modern writers have succeeded in evoking literary power, but we really do need to question it more on a general basis. It may sound like I’m turning on the book, but I personally enjoy any fictional experience that is about the pursuit of enlightenment. As an atheist I don’t really believe in enlightenment on a cosmic level, but I do believe that the deliberate pursuit of wisdom is a noble goal. I tend to lean into the Gnostic/Buddhist interpretation of the process, which is that the material world often causes one to deviate from truly enlightening paths. At this point the natural human obsession with enlightenment is such that it seems the world is covered with cults, all of them eager to sell their own solution to existential issues. But then, the world has always been that way, as I tend to believe the line between cults and mainstream religion is pretty thin. I believe that a true Gnostic or a true Buddhist would understand that even Gnosticism and Buddhism can’t give them all the answers. Truth must come from a study of many disciplines, with a willingness to accept that one’s preconceived notions could always be proven wrong. In a sense, books like this will always be imperfect because the path to learning is a continuous one. There is no end to knowledge, and the only thing we mortals can hope for is to be better than we were before.

VATHIER: Atom is right. I don’t want you, the reader, to think that we disliked the book. Far from it. It’s true that it made me frustrated but I feel that’s why it succeeded . It made for a more active read. Under normal circumstances I would say go buy it but you can’t since it’s out of print. You can always find a second-hand copy but they can be very expensive. I wish Bloom had not salted the earth with his singular fiction book. It’s one of those books that would have benefited from a critical reappraisal.

SARDANAS: Just as the book is challenging to read, our discussion about it is equally challenging to sum up. Appropriate, in a way. It led each of us on interesting tangents – from the spiritual and cultural to the commercial…not a bad legacy for a work of fiction. As it applies to pulp literature, it’s one of very few books with the audacity to ram the academic world and the pulplit world together, and in doing so producing an intense experience. To the authors in our pulp circle who despair about their works being appreciated, I hope you can take heart. Here is a book that the author himself would have liked to suppress, even wipe out of literary memory, and yet all these years later – after crashing and burning in bookstores – it is still being read…still inspiring new efforts to expand the realms of scholarly thought and pulp thrills. If you put your vision out there, amazing things can happen.