If you are so great, then prove it, naked and afraid! If you are so superior, then face life anew, in a new era! To say only the strong survive is your way, but where is the glory of one who never strives to battle their worst demons? Where is the splendor of one who cannot question himself in the dark? – Lutum Hominus, 13th Century Monk

They are called the Dark Ones, the Lords of Antiquity, the Children of Kwo, the Overmasters, the Night Walkers, and most simply, the Gods of Earth. We know them by the black spires that rise from every horizon. We know them by the red sky and the salted earth, and by the second moon which has graced our skies. We know them by the lamentations of our neighbors, which are always in our ears. We know them, perhaps better than we know ourselves.

Why we had the misfortune to be chosen by them, we know not. When we will be free of them, we know not. But we leave scripture, so that one day, perhaps, we will reclaim our chance to step into the great unknown, and touch the stars above.

AACDEGOS V

Two hundred years before the Fall, the Cult of the Union lost the legendary community spirit for which it was renowned and named. Centuries of complex, ritualized emotional interdependence among its members suddenly dissolved when the Cult unanimously voted to begin developing a mutant-weapon for a series of intense mystical conflicts which were believed to erupt in the coming centuries. These conflicts, which were predicted to ultimately result in humanity’s evolution into a spacefaring species in an “Age of Aquarius” event, were difficult to discern even among the most experienced Augurs, and a great ambiguity hung over the proceedings. For the first time in 300 years, a serious disagreement broke out among the members—the argument concerned what sort of mutant-weapon should be crafted for these eventual wars. Some believed that the weapon should be bred hard and rigid, like bronze, able to withstand the bitterness of war through a tough exterior and a bright and masterfully rational mind. Others believed that the weapon should be fluid, protean, capable of adaptation in the face of adversity and open to the potential benefits of chaos. The arguments unexpectedly spiraled out of control, leading to a schism which resulted in the collapse of the Cult of the Union and the creation of the Order of the Aurics (named for their dark, gold-flecked robes) and the Morphic Apostasy (whose symbol was the amoeba).

The Order of the Aurics settled in England in order to distance themselves from the Apostates in America. Here, by invoking the spirits of Degos’lortha, the Brass Eidolon, they spawned the first incarnation of the Eidolon’s child, Aacdegos. Born from the womb of a willing priestess, Aacdegos was a demigod, and so he could not be easily controlled—for many years of his life, especially his adolescence, he tried to return to his father’s realm of Lorthavannia, only to be contained by the amulets and salt-circles of his breeders. In time, he learned to accept his captivity, and when he was old enough he performed his sacred duty, joining with a priest of the Order and impregnating him with the child of a half-god.

The descendants of Aacdegos I grew easier to control with each generation. Their mystical talents ebbed with each generation as well, but the Order was blessed with many gifts while the magic lasted. These gifts proved useful in their increasing skirmishes with the Morphic Apostasy, whom they began to believe would be their primary foe in the upcoming wars.

When a new Aacdegos was born, the life of the previous holder of that name came to an end. He did not die, but went into the world of the spirits, where he rested for but a few moments before passing into the body of his son. His old flesh vanished and he was born into a cut of fresh bronze.

Eventually, the Order produced Aacdegos IV, who was raised by one of the Order’s Inner Circle, a member of the English aristocracy. In order to conceal his connection to Aacdegos, the nobleman in question employed the young man as his secretary. Unfortunately, Aacdegos’ new self proved to be surprisingly rebellious, and he kidnapped his adoptive father’s young son, holding him to ransom in hopes of bringing his masters under his yoke. Aacdegos was eventually exposed as the kidnapper by a London detective, Skeylukkaz Helma, and his assistant Dr. Walda, who were members of a cult distinct from and older than the Cult of the Union and its two primary splinters. To escape justice, or death at Helma’s hands, Aacdegos fled to Australia. Here, he took a human wife, and journeyed with her aboard the sailing ship Hunter’s Belt to the Ocean of Ichor which rings Ma’at, the primary continent and Crown Island of Lorthavannia. On those stinking, churning waves, the wife of the fourth Aacdegos perished as a new form of life ate and clawed its way out of her womb. Before he faded away, Aacdegos glimpsed the face of his new self, whose eye sockets burned with two gold-flecked stars, a fulfillment of the prophecies of old. Even as a child was that face inhuman—in it was nearly a century of learning refined by hammer-hard force into a being of meticulous logic. That starry-eyed child grew up alone on the Hunter’s Belt, under his father-ancestor’s tapestry of foul and distant stars, which whispered to him as he slumbered in his cot.

When he walked among the world of humans, delivered by his ancestor’s fell angels, he swayed men to his cause. He built a personal army of those who were soul-joined to him, becoming his human familiars, recipients of his passions and displeasures. These he refined as he himself had been refined. In this time he also won consorts among Earth’s women, but they failed to satisfy him, and so he pulled from his own stone-hard flesh his rib, and from it grew a golden-eyed woman who stood tall and strong. Though this being was effectively his daughter, his sister, or at best, a kind of cousin, she became his bride, and their matings, held in the high lofts of Lorthavannia, were the sort of perverse thing to drive a witness to them mad.

Like the others of his kind, Aacdegos glutted himself upon the spilled blood of war, and so became bloated and strange in the wake of the Fall.

AFTER THE FALL: Aacdegos is the reason why our mates are chosen for us, and why the meat we eat comes from the children who are born imperfect. Those who worship him, such as the New Auric Order, the Templars of Science, and the Sons of Ham, believe that he is guiding us towards genetic and philosophical perfection, by killing off all that which is like his age-old rival, Aeeeghnrt. For most, this hardly justifies the millions who have died in his temples receiving his “Cure,” which removes from those few who survive both criminal tendencies and free will.

He has bred with Aanrtz, Adehhost’w-Deehiprst, and even the hated Aeeeghnrt, with whom he mated when their hatred could not be expressed by mere fighting. With Aarntz he has fathered Deraat, the hulking God of Incest; with Adehhost’w-Deehiprst, D’chaose, who is called Pandemonium’s Herald; and with Aeeeghnrt, Gd’eaagn, the GOD OF ALL THAT IS AND EVER WILL BE.

AANRTZ

The Ocean of Ichor bridges the world of Lorthavannia to that of Lewkidos, where even gods fear to tread. Lewkidos has no ruler, but it serves its own purposes—some of which are still cryptic, even to the wisest Sages.

On Earth, long ago, a husband and his pregnant wife were guests aboard the leisure ship, sailing the blue Atlantic and enjoying the peacefulness around them. The First Mate stepped out onto the deck and saluted his Captain. Then, he made a quiet prayer to Ippigo, the Poison Animal God, and calmly slashed the Captain’s throat. As the man and his wife screamed before the horrible sight, the Mate seized the wheel and a great storm brewed, which, under the Mate’s command, carried them into darkness onto the oozing green of the Ocean of Ichor. Here, he set to sailing west for distant lands.

Upon recovering from the shock of the ordeal, the terrified crew mutinied to try to bring their vessel back to Earth where it belonged. But as they neared the shores of Lewkidos—which the Mate called home—they began to turn on each other, peeling flesh from each other’s bones with naught but their bare fingernails. The man, Johann, and his wife, Lady Alicia, decided to take their chances with the ooze, and upon jumping overboard they tried to swim to land. Maybe they didn’t choose it—maybe it was just blind panic, a panic so terrible it made them forget even their unborn child.

The “swim” through the awful slime was far worse than they could have imagined. The stench was beyond nauseating, and their clothing was no defense against it. It clung to their skin, freezing their flesh pale until it was like that of corpses. Small claws and the lips of eyeless fishes nibbled at their limbs. When at last they emerged and stepped on the cracked stone beachhead of Lewkidos, Lady Alicia knew that the ichor had found its way inside her, and her child was likely dead—or worse. Somehow, her senses told her that her baby still lived. But she nearly hated such a prospect, for what the slime must have done to the growing fetus.

A bitter, acidic wind blew from the east, the aged remnants of a time-old barrier meant to keep Lewkidos contained. Millennia ago this wind was like a hurricane, and it blew a sour rain that burned the flesh of even the hardiest species. Now it was just enough to force mortal humans into the flesh-jungles for shelter, even if it did not stop the Great Beasts from emerging.

In the jungles of Lewkidos there is no light. The sunlight ceases to exist there, being swallowed by the devourer-leaves of the upper treeline. Though their eyes eventually developed to cope with the darkness, Johann and his wife were left almost totally blind for the meager remainder of their lives. Their ears became their only defense, for there were things in the jungle waiting for them, things which were like nothing on Earth and had none of the kindness of any Earth creature. Somehow, through the merit of a stone spear, the pair survived long enough for the Lady Alicia to give birth. As pain ravaged her starving body, she was thankful she could not see her child, for as it moved down inside her she could feel it had too many limbs and that its skin was rough and hairy. In time, Aanrtz would discard this form for something more like his parents, but when he was born, he squalled with a voice more like that of a broken toad than any human child.

For the first time in what felt like lifetimes, Johann saw light. A pale gray light came from the newborn’s eyes, which glared at him unblinking from the first moment of its birth.

Months passed. Johann buried his wife, and he fought hard when the Grey Ghouls came for his son. But all men die, and Aanrtz, named for the first “word” he spoke, probably belonged among those bony, cadaver-cold forest folk anyway.

The Grey Ghouls, the ghosts of the forest, raised him in all their practices—they taught him to howl at the unseen moons of Lewkidos, who they knew only by their celestial stink; they taught him what the hunger-wasp knows, and what the fanged listonfish sees. They gave him all of their rituals and baptisms, and they brought him before the lovely and terrible Pale Priestess who dwells in her golden city, built by the pseudohuman shadows who now linger beast-like in its darkened corners.

Now Lewkidos is no longer unknown; we are not safe from the knowledge of it. When the Fall came, people remembered Lewkidos, and it became part of the Earth. It erased the countries of living, thriving people, and in their place were planted the seeds of greed, colonialism, and destruction. Many powerful men were driven mad, and fled into the jungles of the newfound land, in hopes of becoming masters of the people and treasures there. But instead, Aanrtz was waiting for them, and he fed upon those who fell into his snares.

AFTER THE FALL: Lewkidos spread over much of the Earth, infecting and tainting it, but Aarntz left its flesh-jungles long ago. He has since begun living among men, watching us and testing us, baiting us. He whispers in the ears of Generals and Kings, telling them to steal and kill and rape and desecrate. They go to lands in his name and make slaves of the people, and through his incantations he makes them believe they are free. When they resist this impulse they are killed or made into objects. He is hailed as a hero of myth and a symbol of glory and male strength, and his face adorns many statues and reliefs.

He has mated with Adehhost’w-Deehiprst and Aeeeghnrt, and with Aacdegos, as mentioned above. With Adehhost’w-Deehiprst, he has sired Drotha, the Night Stalker, and with Aeeeghnrt, he has parented Aeneth, the Grey Seductress.

ADEHHOST’W-DEEHIPRST

Sometimes called the Twin-Who-Is-One, Adehhost’w-Deehiprst’s origins were murky for the majority of his existence, and they remain murky still. The pieces only started to fall into place when it was confirmed that he was first sighted at a village bazaar on the slope of Mt. Arra in the Nameless Nation, a diplomatic neutral zone established at an inconstant, ever-shifting location in the Southern hemisphere in the wake of the Konshalin Wars. Historical records indicate that his appearance coincided with the efforts of a local occultist group, the Unnameable Veil, to harvest the remnant emotional negativity of the Wars to create a tulpa that would do their bidding. The Veil was made up of wealthy white men who had come to the Nameless Nation and adopted rituals which they believed were representative of the “primitive” people of the region. In truth, they had made up these rituals from their racist stereotypes; but all rituals are made up, and so they were able to find real power in them so long as they gave strength to them, and ignorance can create its own strength. As they gained power from their magic, they attempted to exoticize themselves, taking the bastardized trappings of a dozen cultures and grotesquely syncretizing them into an unrecognizable mess. They insulted nearly all the oppressed peoples of the world in their attempts to make themselves an alien peril on Earth.

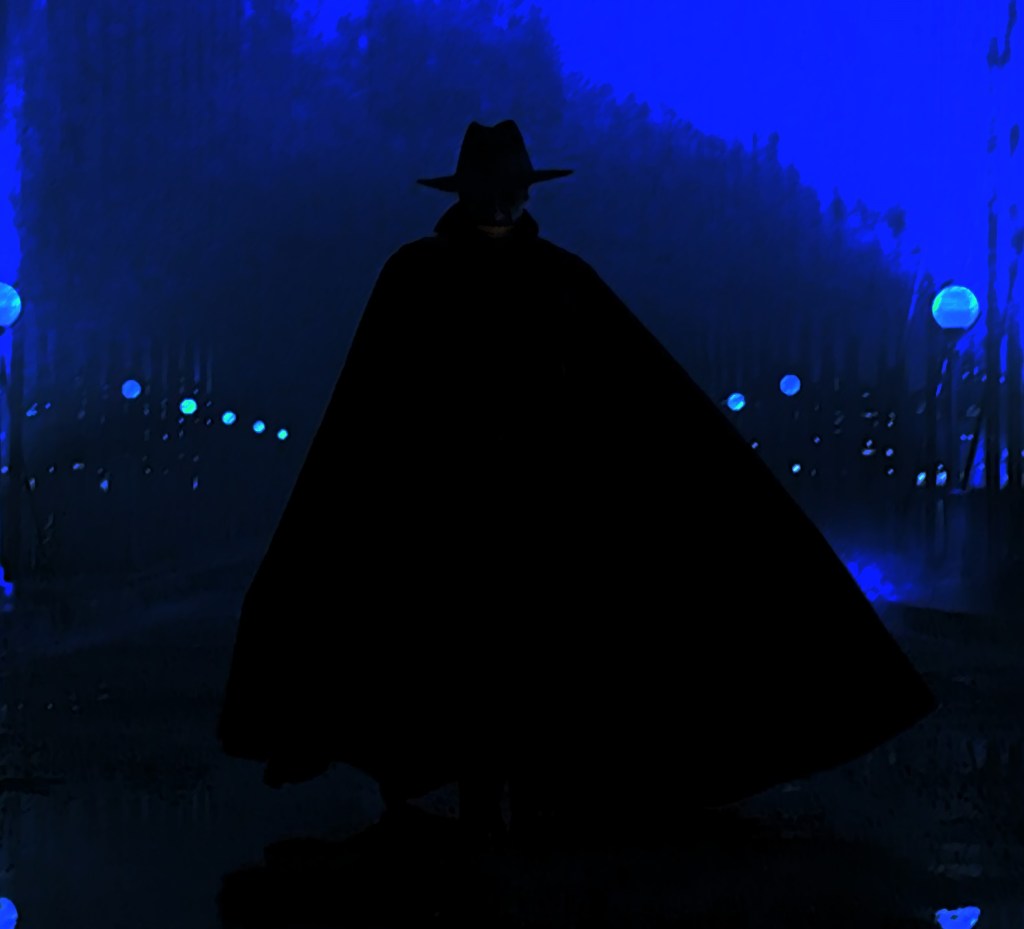

Their tulpa experiments involved an effort to call forth spirits from what they called the Abominable Emptiness—a well of misery that was an incarnation of all of humanity’s base instincts and vulgar inadequacies. They opened a gate, but they did so incorrectly. The breach entered our world explosively, destroying the Unnameable Veil’s stolen temple and causing a fire which nearly burned down the forests of Mt. Arra, until a rainstorm intervened. A stranger clad in black walked down the mountain as the rains came down; a single remaining priest, whose name was Raymond Ginger but who had styled himself Raji, walked with him, held in thrall.

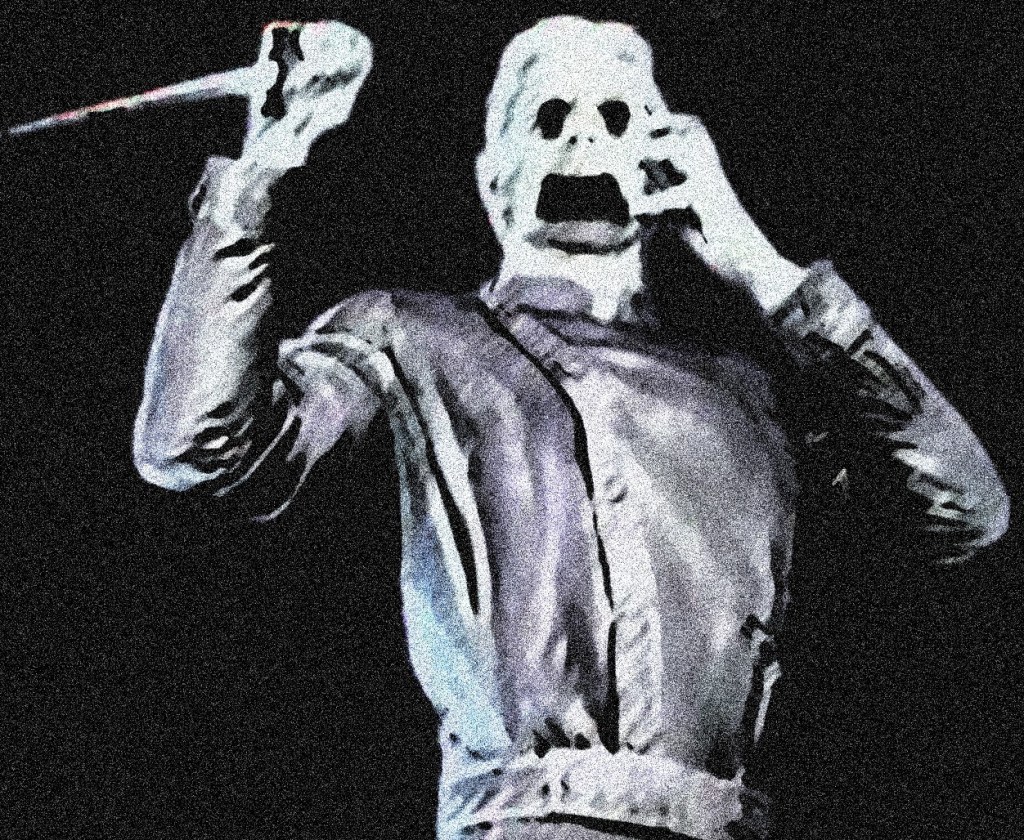

Adehhost’w-Deehiprst lives in eternal pain, for he is two tulpas bound into one. He tugs at himself, gnaws at himself, and his thoughts betray him constantly. He is as a man with two heads, and he has endured this for so long that he has become pitiless, even to himself. He no longer laments his pain; he laughs as it. And he laughs as he takes the lives of others. He spared that bazaar in the Nameless Nation—he spared all those he met as he made his way to New York. But once he had established his nest in New York, using a whispering, shapeless bhoot called B’rr’b’nk to recruit an army of agents, then his true self emerged. He kills all he finds, good and evil and neutral alike, save for those he has deemed loyal to him. To avoid killing exhausts him; the journey to the home of his spider’s-lair nearly killed him, for he could not kill those who were transporting him to the destined place.

He kills and kills and kills, sometimes with the enslaved Raji by his side—sometimes a beautiful, unsmiling woman. With guns, kukris, and his naked hands, he kills. And as he kills, he screams in pain.

Only it emerges from his lips as a cruel and mocking laugh.

AFTER THE FALL:

HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHHHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA! HAHA! HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHHHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA! HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHHAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA

AEEEGHNRT V

For all of their hatred of each other, the Order of the Aurics and the Morphic Apostasy performed their rituals and developed their mutant-weapons in almost perfect parallel with each other. Indeed, their symmetry was so perfect that it almost certainly could not happen without some sort of occult superstructure guiding their actions. It seems that the Cult of the Union, in truth, remained unified when it broke in two—it fell divided, but not wholly sundered. Each of its halves represented opposing future potentialities, not only for the Cult’s future, but for the future of the world at large. These potentialities, contradictory though they were, were part of the Union which had made the Cult so strong to begin with.

During its peak, the Cult of the Union derived its power not merely from the mystically-woven friendships among its members, but from the antitheses which emerged from those friendships. The Cult was made of those who would not be friends in any other life. Sometimes there are people who are destined to never be friends, only tolerant acquaintances. Experience is a hard thing to share in a life that is mortally short. But the Cult made them friends, and joined their contrary experiences. The prophecy of the coming wars only served to realize a conflict which had been buried the whole time; yet, it had been that very conflict which had allowed the Cult to thrive. The tensions between the two factions within the Cult joined with the rituals of Unification to create the miracle of compromise. And it was the kind of golden compromise that discards bias, bigotry, selfishness, and shortsightedness, rather than yielding to them. That compromise was destroyed and lost to the world when the Union Cult fell.

The High Council of the Morphic Apostasy somehow became aware of the paradoxical symmetry that bound them to their enemies around the same time that they were raising Aeeeghnrt II. By then it was too late for the two cults to form back into one; even if they wanted to end their fight, the curses they had cast on each other’s members would destroy them if they tried to come together again. It was also too late to abandon their experiments, for Aeeeghnrt was now a parallel to Aacdegos, and they would be joined together until fully realized in their fifth incarnation. Aeeeghnrt was the son of Ghnrt’thogos, the Froth Toad, who is considered by most to be Degos’lortha’s grim nemesis. Aeeeghnrt’s soul developed on the plane of Thogos’akma, the Froth Toad’s domain, where the night-lilies sing an eerie and seductive song, and the pond waters sparkle with fae-light.

The Apostasy decided that paradox could be the secret to dominating the Auric Order. Soon they desired to infuse the raw power of paradox itself into Aeeeghnrt. For this they rejected Ghnrt’thogos, and all other aspects of their child’s origin. They would force their experiment to merge with something he was not; they would force him to become what he was not. They reached out to the Abominable Emptiness, probing as deep as they could into it, until they found its meta-structure, the true embodiment of emptiness: the Mauvalla, the purple heart of Nothing itself. The cult bid Aeeeghnrt II to walk into the violet contradiction, to un-be, to undo all he was.

Aeeeghnrt II walked in, and he walked out again. But he did not come out the same.

Aeeeghnrt was born in the form of a handsome Black child with piercing dark blue eyes. Now, his skin and hair were stripped of their color, though his African-seeming features remained. His dark blue eyes now shined pale, and the smile which had often gifted his lips was now permanently gone.

Aeeeghnrt hated his fellow Apostates then—but his face would not twist to show his rage. For his face was frozen by all he had seen and done in the eternities he spent within that awful place.

He continued to live among them. He allowed himself to be married to a woman, who would bear what would be his next self. When she began to give birth, he slowly began to fade away, as he and Aacdegos both did when their newborn incarnation emerged.

But as the priestess gave birth, she felt her pain release suddenly, and all her muscles relaxed. It was the last thing she ever felt—a brief bliss.

To the observing doctors, it seemed as though she had birthed…nothing. But the child had been born. He was born a living virus, an invisible shape with no true form. He surged into his mother’s cells, replacing all of them in a single instant. She perished, and he, in her shape, took her place.

There was great confusion, and the priestess, whose womb was as one who had never been pregnant, was taken away for questioning. Her questioners never left the interview room. But a man who looked like one of them walked out, adjusting a necktie which was in truth made of skin.

Aeeeghnrt III was his own master, and when he spawned, he did so by himself, splitting into two. The new, superior Aeeeghnrt IV devoured his predecessor, taking his strength as he did so. Such would be his own fate, he knew, when Aeeeghnrt V was at last born.

A madman named Rex Blessed, a patient at St. Bemliko’s Psychiatric Hospital (sometimes called the “Nightmare Castle”), became Aeeeeghnrt’s permanent form. A lifetime of devotion to the gods of Lorthavannia, Thogos’akam, Lmnr’rrr, and other unholy lands rewarded him at last. Since then, with Blessed’s face, Aeeeghnrt V has walked the Earth, long desiring dominance over his parallel counterpart—and the rest of the world.

AFTER THE FALL: Ever since the Dark Ones caused the Fall, and grew vast and different, Aeeeghnrt has fought an increasingly losing battle against his rival, Aacdegos. His sigils and formalities are more complex than those of Aacdegos, and so they are not so readily embraced. Those who devote themselves to him gain more might than those of Aacdegos, some even becoming talented shapeshifters—but his worshippers are infected with a curse which slowly transforms them into the cephalopodic “Voidminders,” which are incapable of thinking.

Nevertheless, he has mated with Aacdegos, as well as with Aanrtz, and with Adehhost’w-Deehiprst, producing the Lord of Dark Places, Adgn-hotet. Adgn-hotet is currently the only spawn of the Dark Ones to take a mate, having married Hs’Tod Dei, Lady Noxebrae, the self-bred offspring of Adehhost’w-Deehiprst. Their child, Asgodht, waits patiently until the day he can force his uncle G’deeagn into one of his thousand mouths.