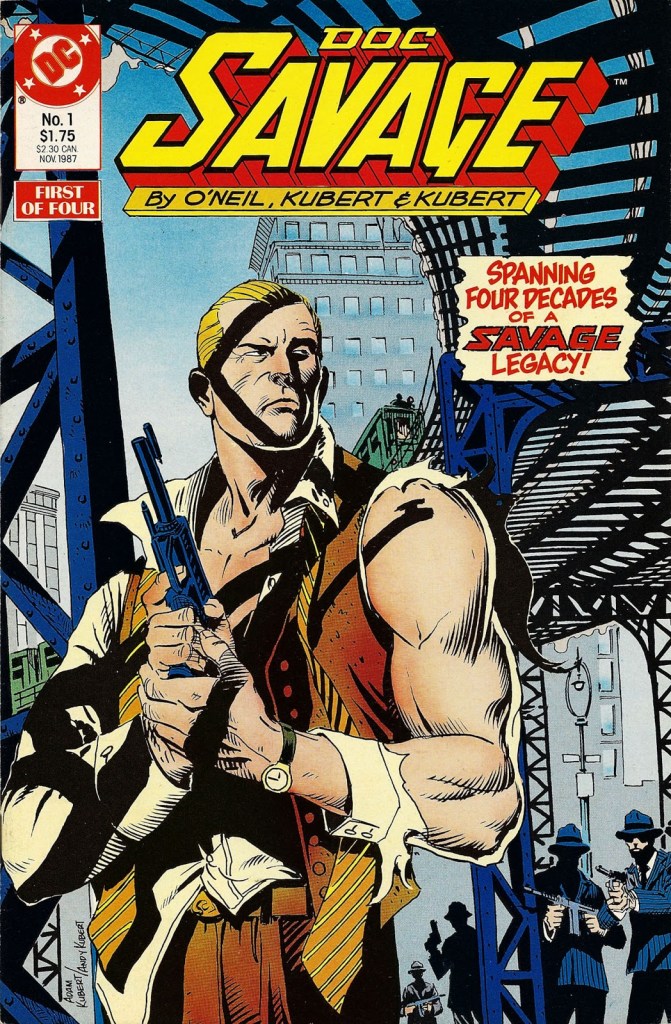

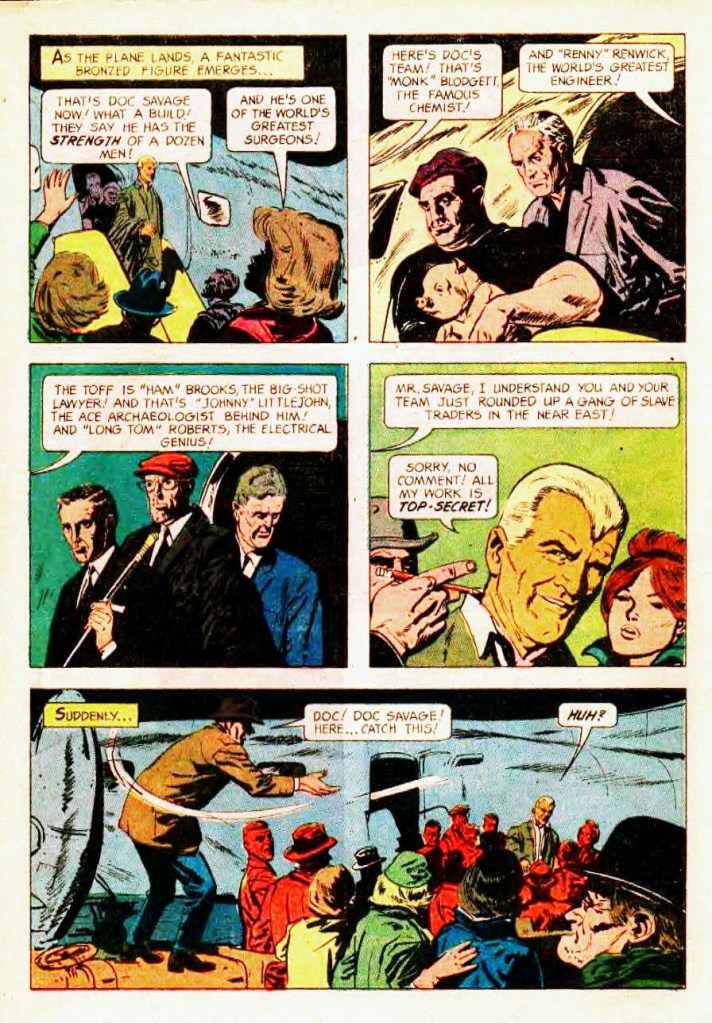

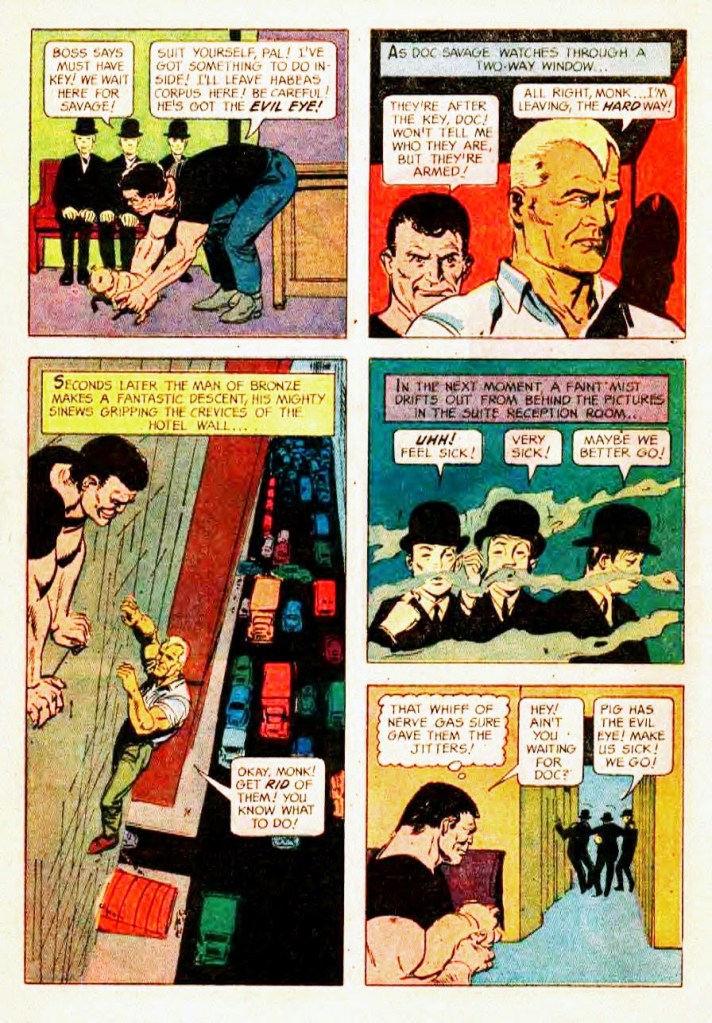

The first two parts of this article were in chronological order, exploring the characterization and presentation of Princess Monja in the 1972 Marvel Doc Savage comic, and the 1987 DC comics series. Monja would next appear in the 90’s, when Millennium, a smaller but very ambitious comics company, acquired the Doc Savage rights.

Millennium’s series will be the final installment of this revisit to the Princess Monja of the comics. First we will jump all the way forward to 2015, and the most recent appearance of the princess, in Dynamite Entertainment’s miniseries The Spider’s Web.

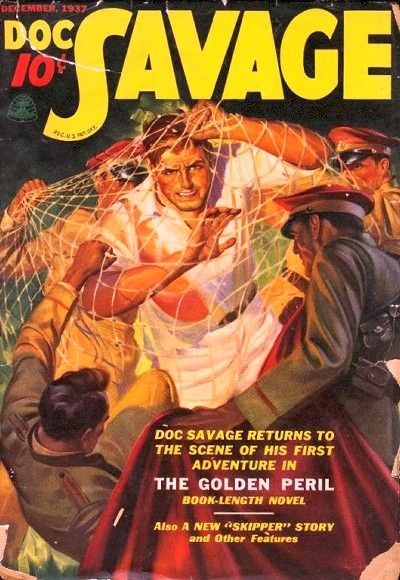

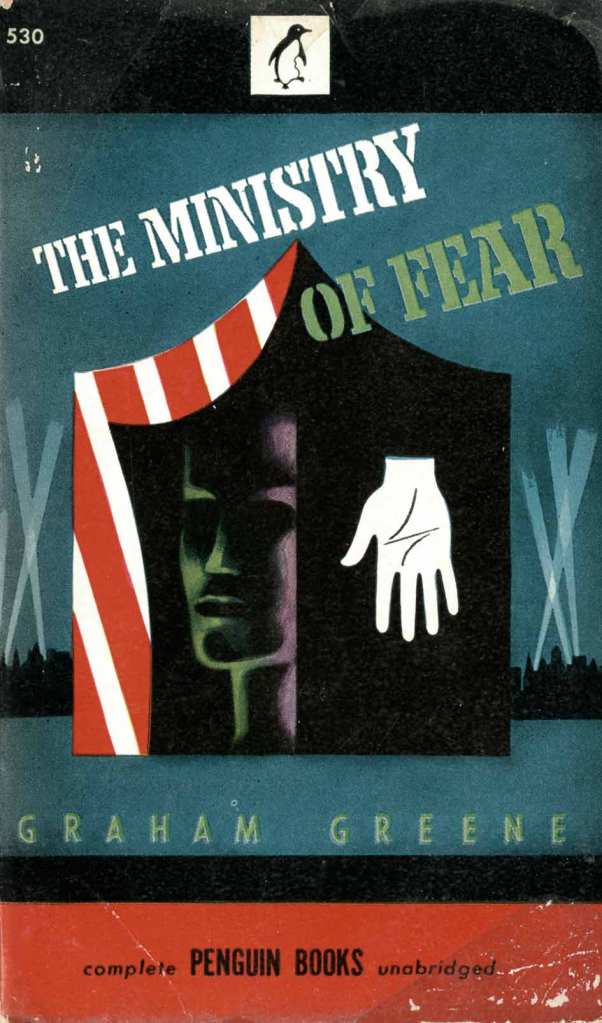

The writer/artist team for this five-issue series (specifically designed in length to be collected as a single graphic novel), was Chris Roberson and Cezar Razek. Prior to The Spider’s Web, Dynamite and author Roberson had done a much larger limited series (with impressive Bama-like covers by Alex Ross), in which the whole mythos and timeline of Doc Savage was hugely overhauled to cover the entirety of the 20th Century and beyond, to the present day. Doc’s aging (and to a lesser extent, Pat’s) has been arrested, not through the technology of space aliens as in the DC series, but through the use of silphium, the chemical that first appeared in the original pulp novel Fear Cay. This gave Roberson a huge swath of time to play with in his subsequent series.

Interesting, and certainly ambitious, but the Dynamite series seemed to try and chart a middle road between exuberant pulp adventure and the more complex plotting of modern thrillers…in the end feeling surprisingly flat.

The Spider’s Web uses the new framework to the Doc mythos to tell a story spanning much of the century. While certainly a competent tale, it is cluttered with characters that seem to serve very little purpose beyond moving the plot to the next stage. Among them, Princess Monja.

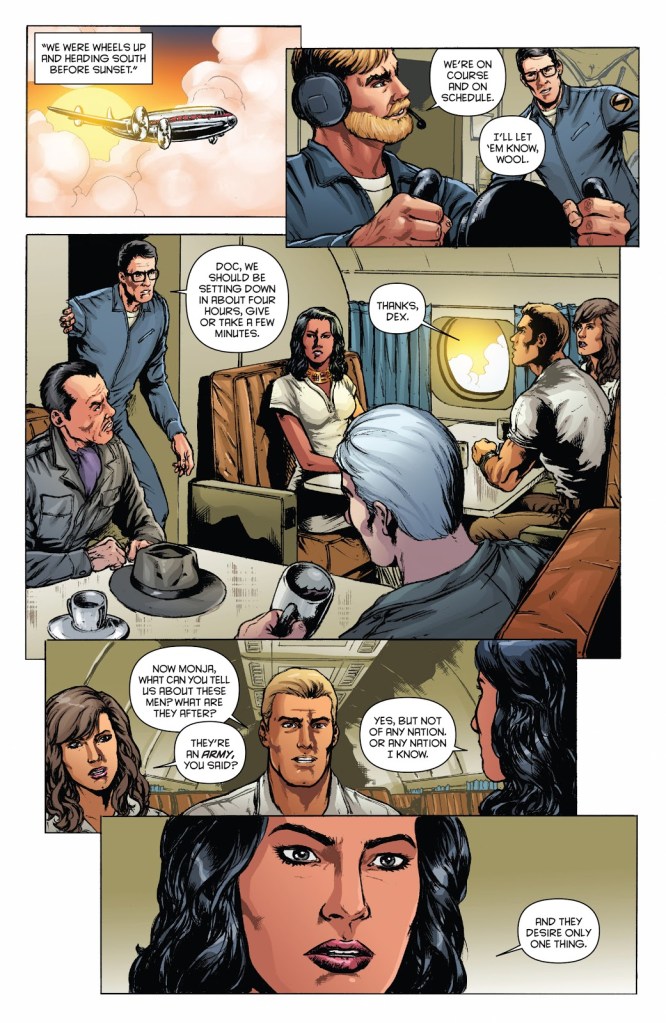

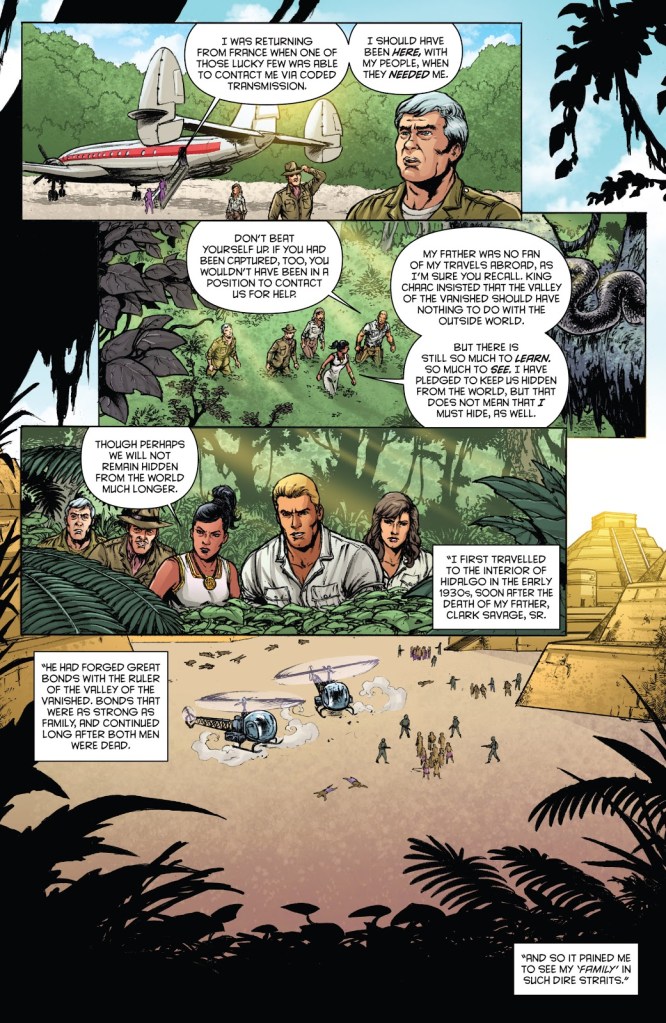

The segment of the story she appears in takes place in 1955 — an intriguing notion in and of itself, as that was beyond the 1949 end date of the pulp adventures, but far enough back in time to potentially have a unique period feel. It is presented as a flashback (Doc and his new collection of assistants are working their way through the 20th Century for clues to a modern-day mystery). The basic plot is a small mercenary group has taken over The Valley of the Vanished for nefarious reasons.

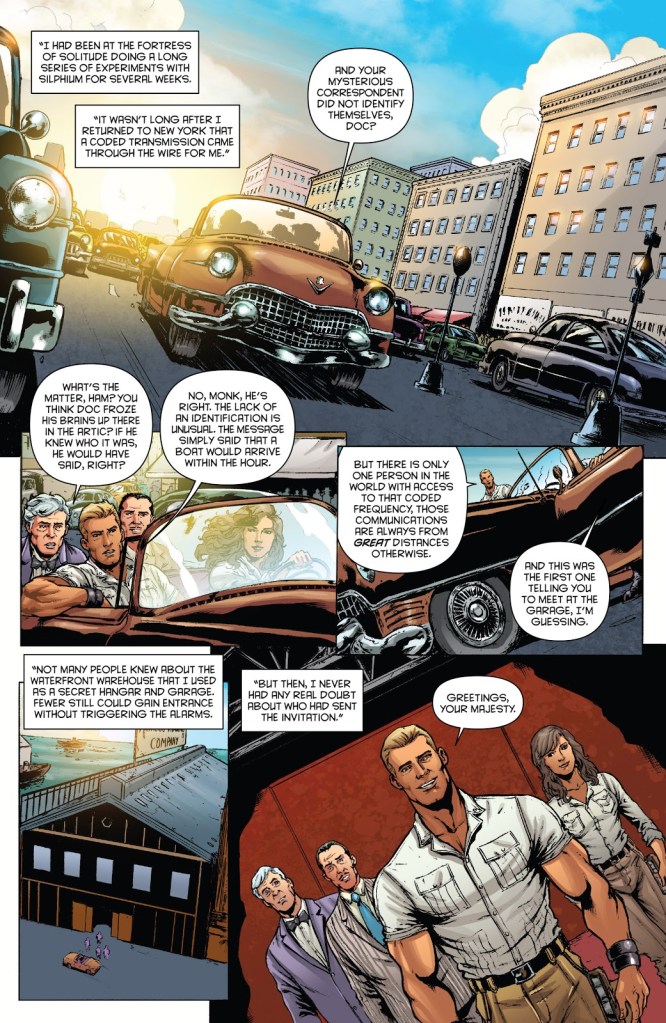

Doc, an older Monk and Ham, and Pat drive out to the Hidalgo Trading Company, doing a fair amount of talking to set the scene (a recurring problem with the Dynamite comics, contributing their often static feel).

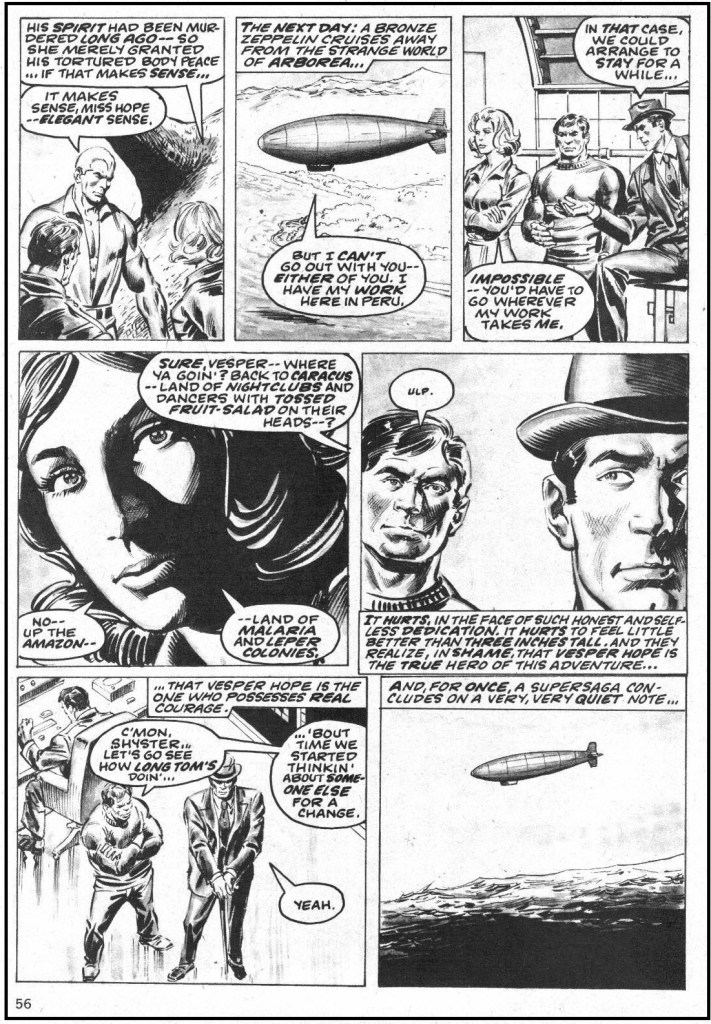

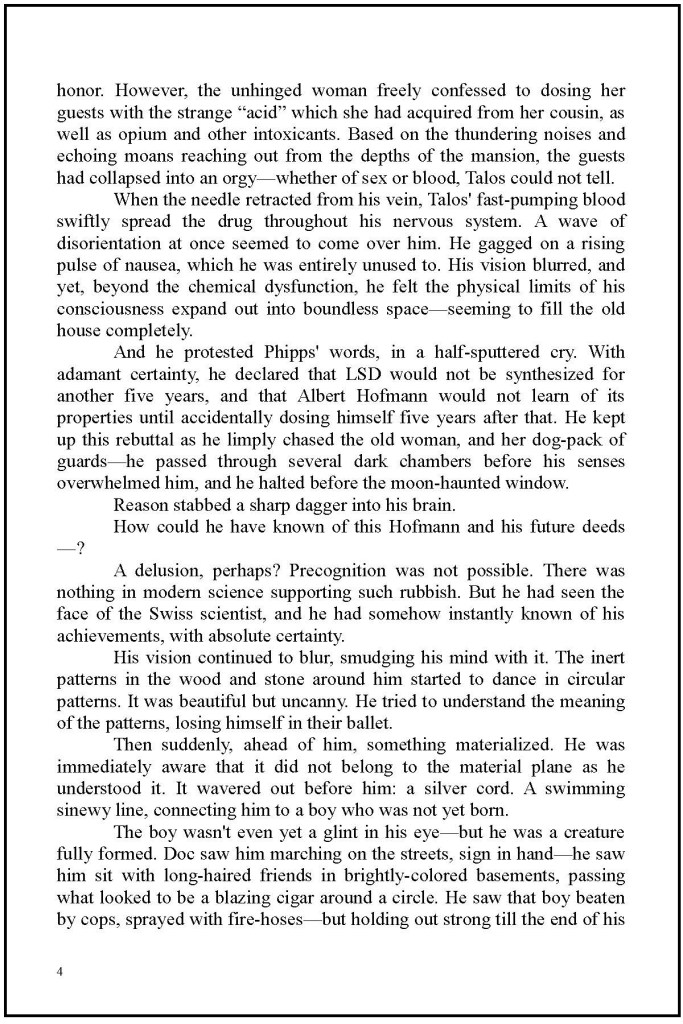

Upon arrival, they find their guest to be Monja, who is quite unlike any other incarnation of the Mayan princess.

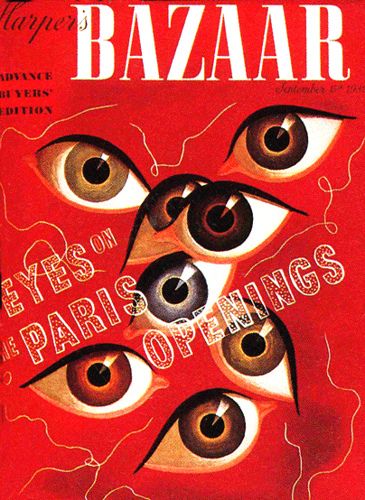

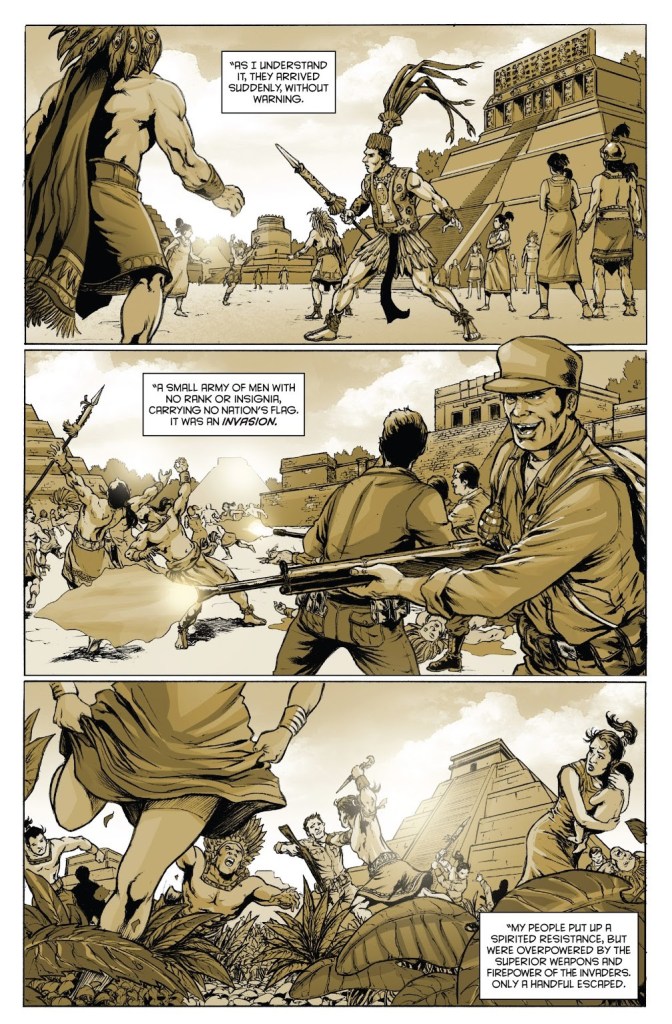

She is now Queen Monja, not princess. She’s sophisticated, modern, emotionally cool. And from the get-go it is clear that it is not merely an exterior demeanor; she and Doc have no intimacy, no spark to their relationship. He greets her by shaking her hand…even Pat is warmer, giving her a hug and calling her “Monnie”. She talks about a recent sojourn in Paris, and her other travels abroad. Then they get right down to business (more sitting and talking, again lapsing into exposition). Monja tells them about a mercenary invasion that has happened in Hidalgo, and enlists Doc’s help in freeing the Valley of the Vanished from that oppression.

A page later they are in Hidalgo, and setting off into the jungle.

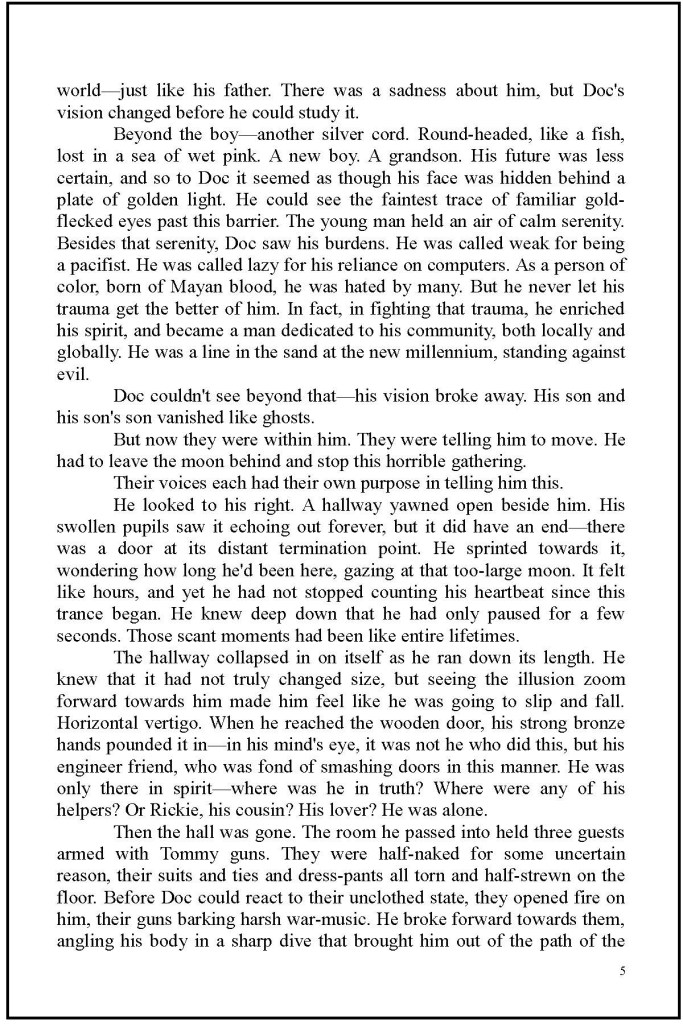

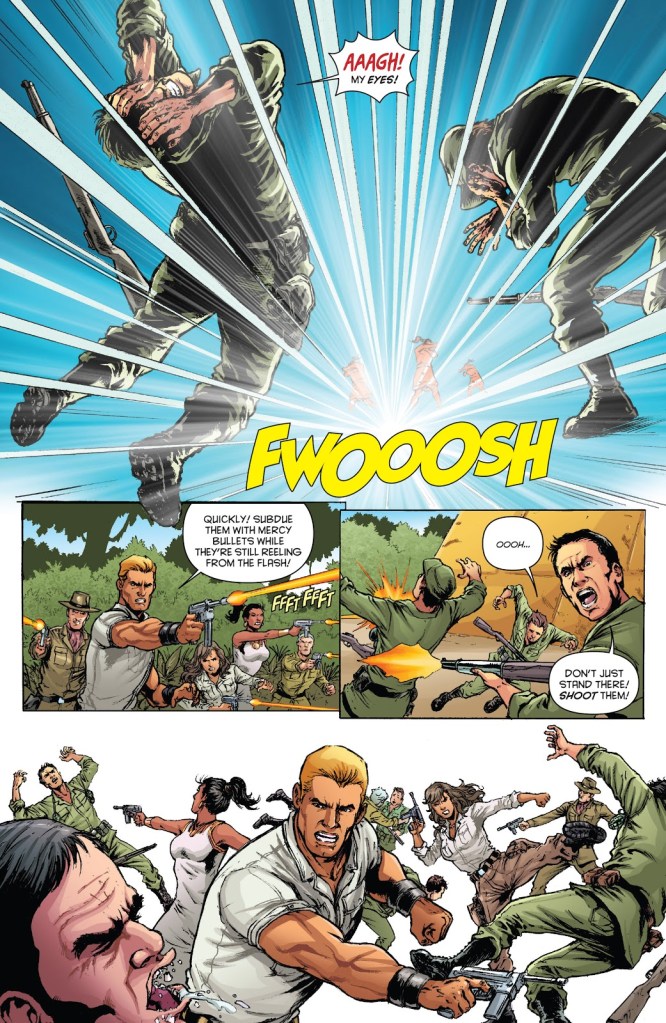

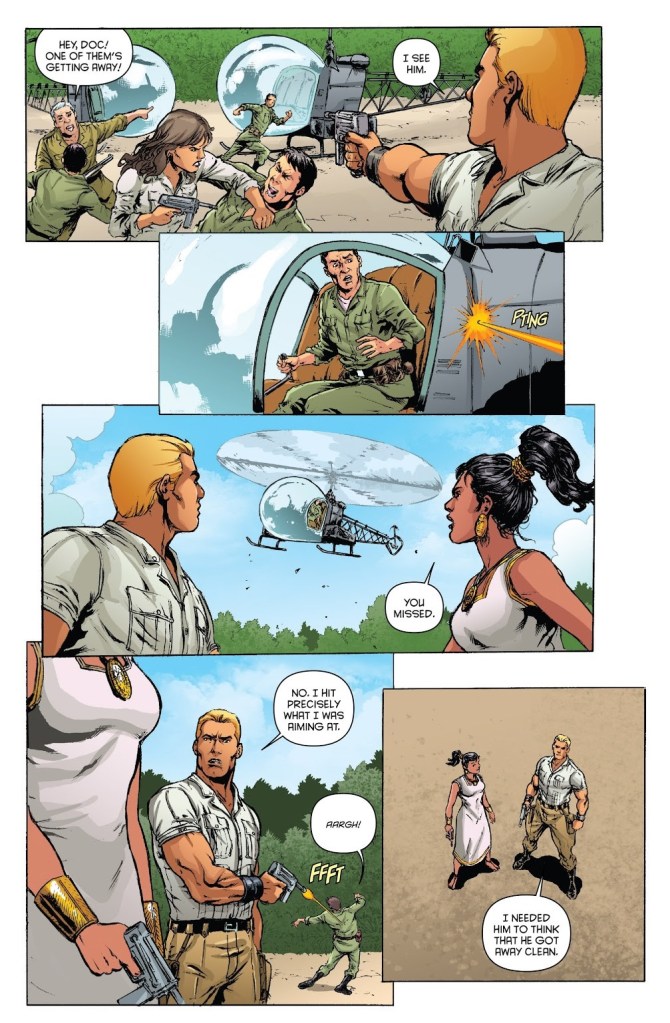

The fight that ensues is brief, decisive, and over before you know it. Monja, during the course of the battle, is strong and handles a pistol with authority — no trace of the tragic heroine, which I found enjoyable — but also, pretty devoid of personality.

The mercenaries are routed, the plot is advanced to the next stage, and the final panel with Monja shows her standing near to Doc but apart, in a state of visual and narrative disconnection.

And that’s it. She does not appear in the story again. Once again, potential to explore the more human side of Doc through his connection to Monja comes to pretty much nothing, which I found sad. The story lurches on its way, and through many laborious machinations winds back to the present…all told — to use the same descriptive as above — competently, but absent of storytelling fire.

Hard to say if this will be the last time we ever see Monja in the comics…the next Dynamite miniseries didn’t include her in any way, and Dynamite does not seem in any hurry to do more Doc Savage. “Modern Monja” certainly has potential, but in what seems to be her constant fate, it may well remain unrealized.

Next…Monja’s most emotional and intense incarnation, in the Millennium story The Monarch of Armageddon.

To be continued…