In Jeff Deischer’s recent guest blog post here at Forbidden Pulp, he introduced Doc Brazen, his unique pastiche series based on the adventures of classic pulp hero Doc Savage. I was also honored to write the Introduction to the newest edition of the first book in the Doc Brazen series, Millennium Bug.

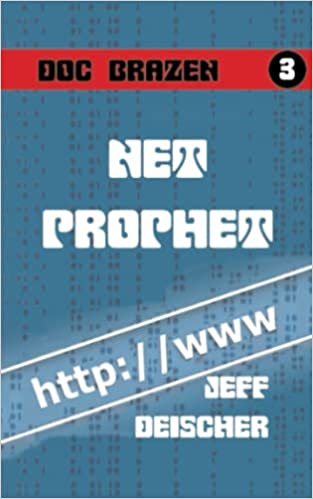

The exciting news is that Doc Brazen is back! The new Brazen novel, Net Prophet, is now available.

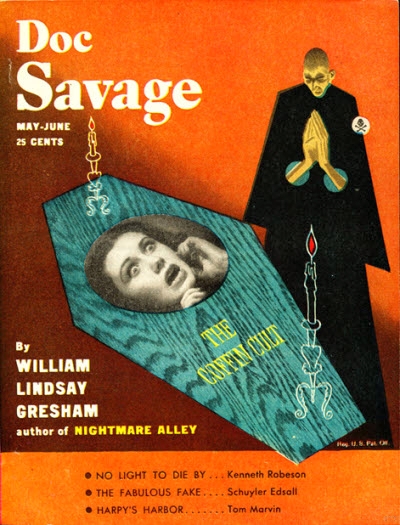

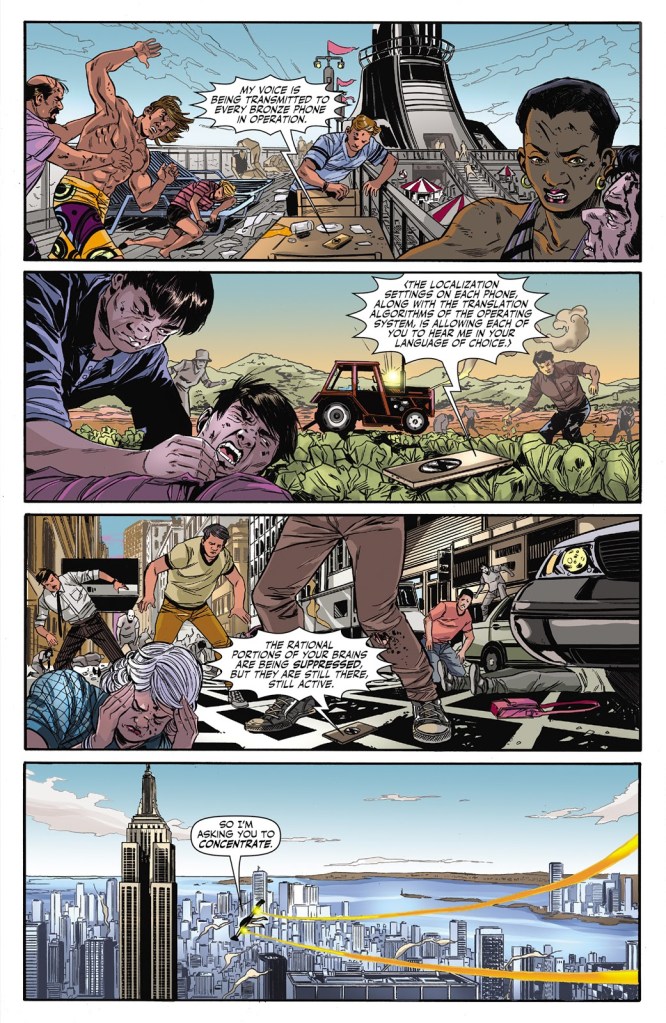

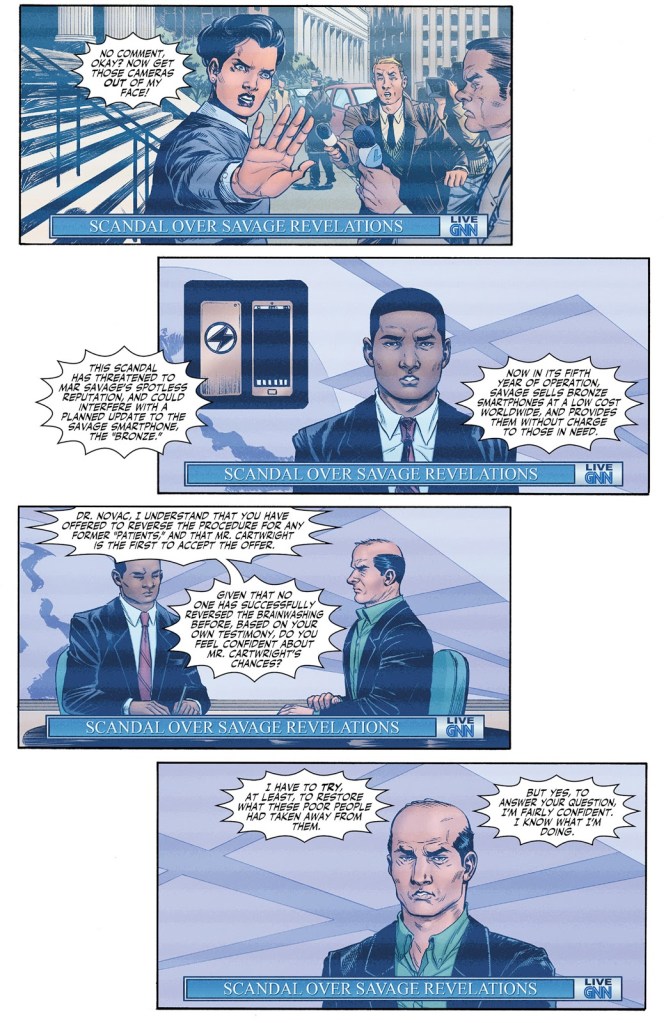

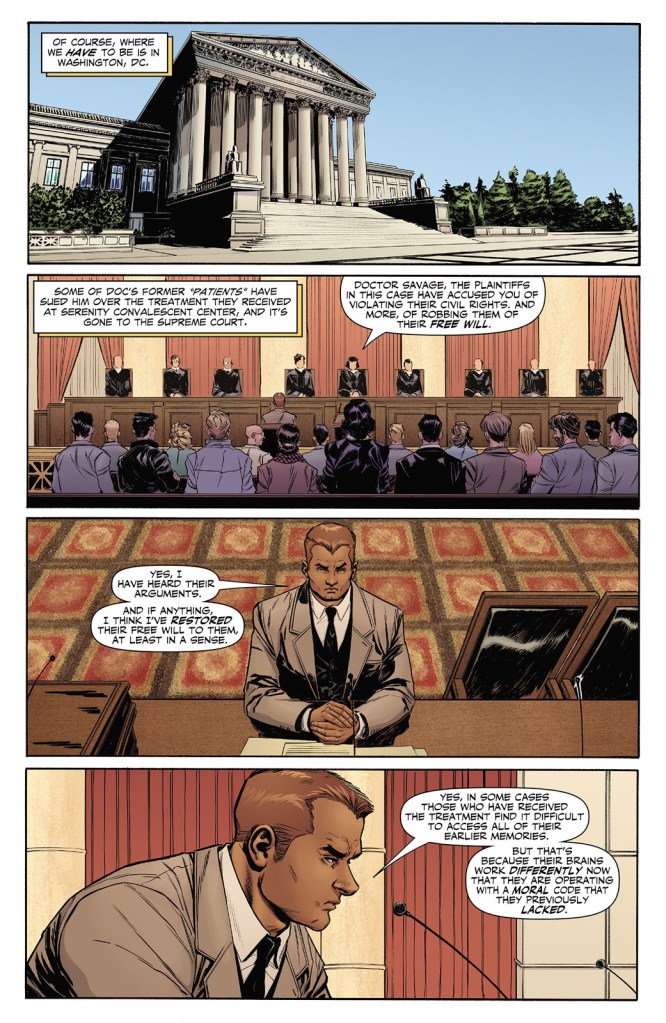

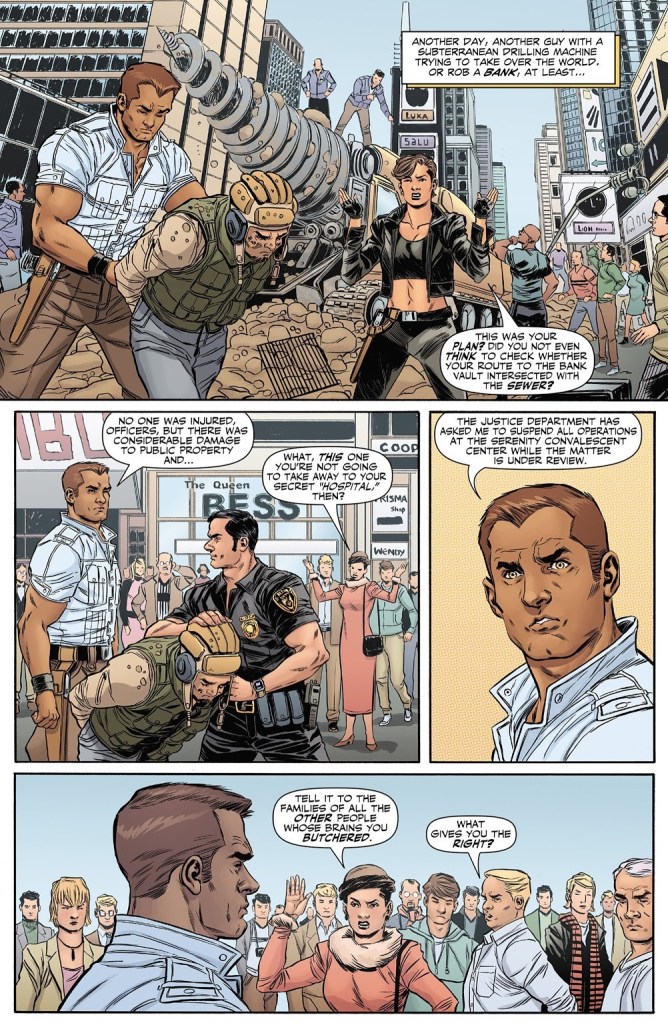

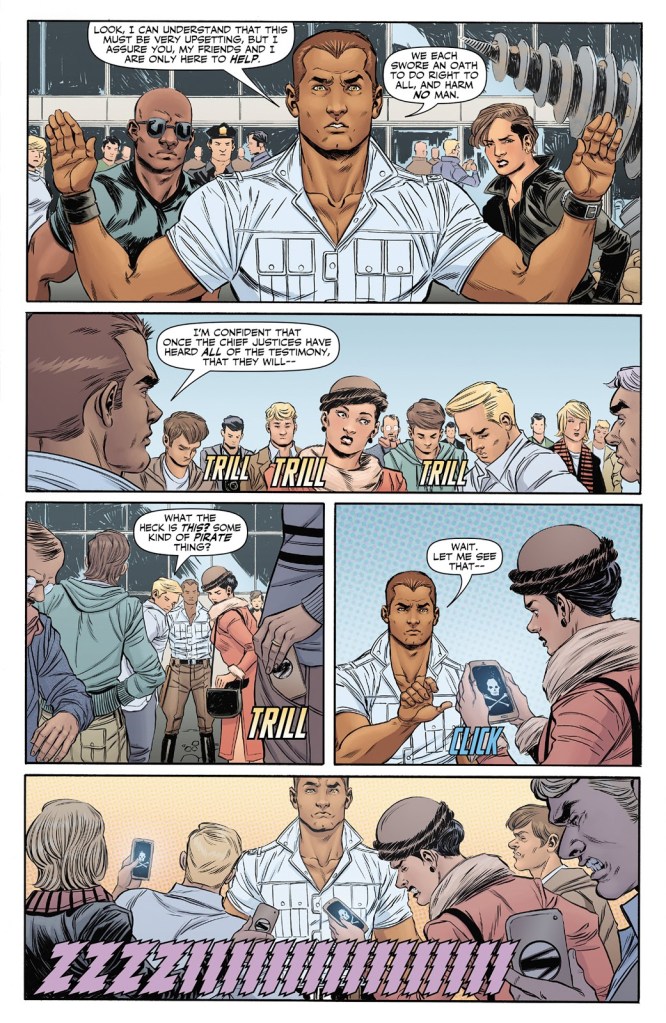

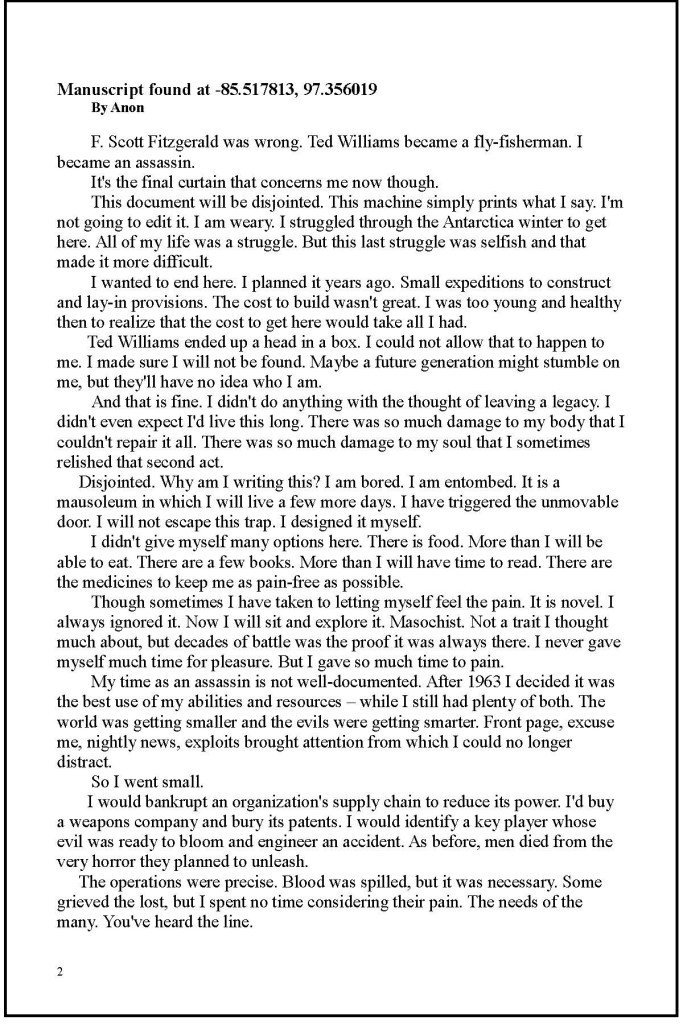

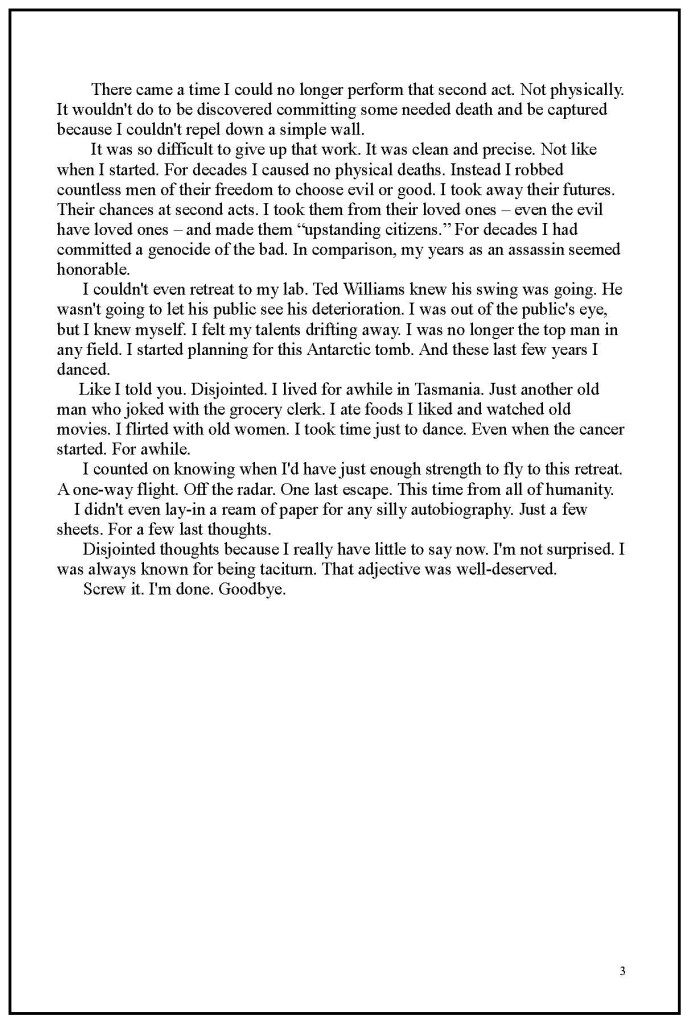

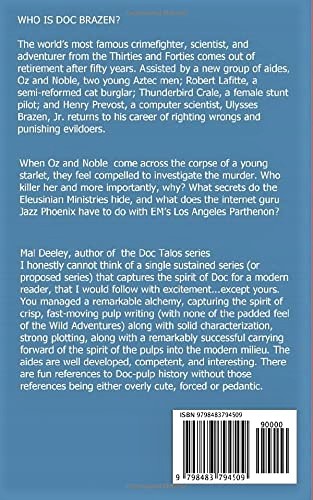

Here is the book’s description, and a look at the front and back cover:

WHO IS DOC BRAZEN?

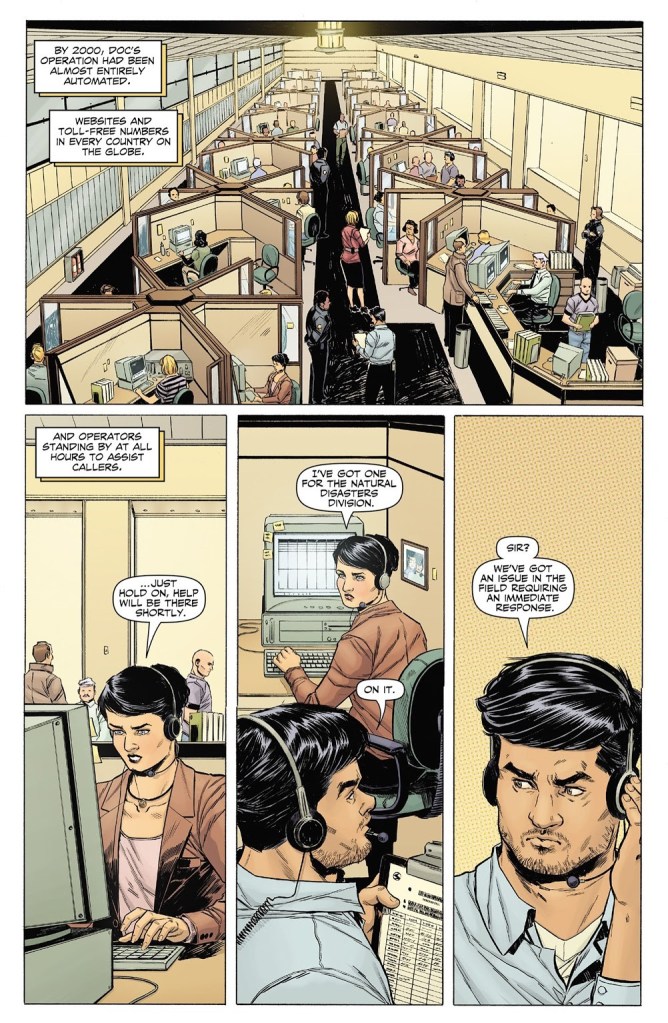

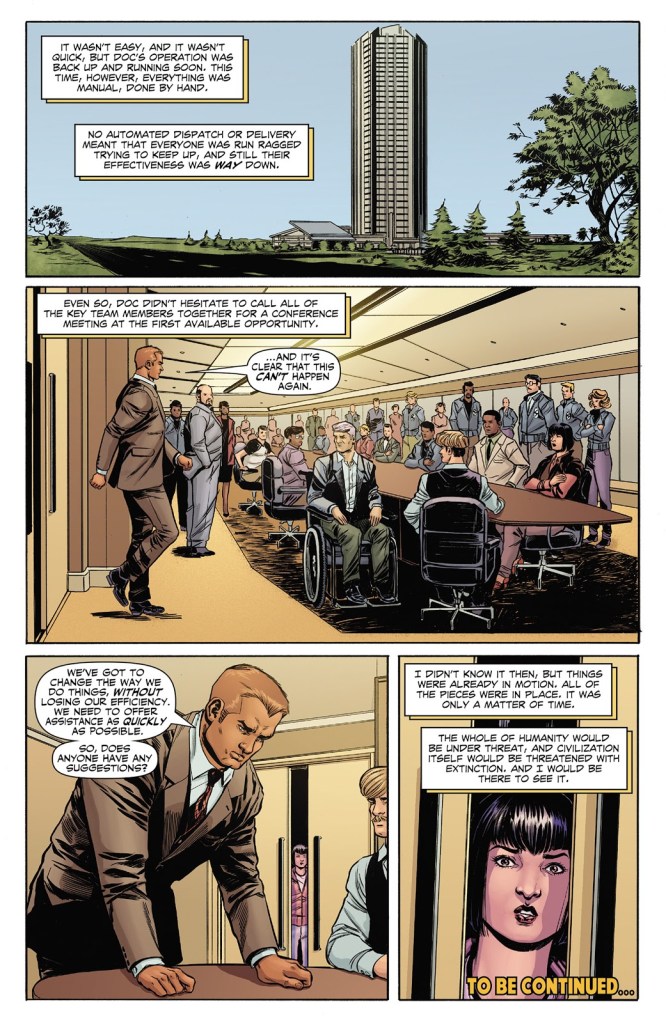

The world’s most famous crimefighter, scientist, and adventurer from the Thirties and Forties comes out of retirement after fifty years. Aided by a new group of aides, Oz and Noble, two young Aztec men; Robert Lafitte, a semi-reformed cat burglar; Thunderbird Crale, a female stunt pilot; and Henry Prevost, a computer scientist, Ulysses Brazen, Jr. returns to his career of righting wrongs and punishing evildoers.

When Oz and Noble come across the corpse of a young starlet in unusual circumstances, they feel compelled to investigate the murder. Who killer her and more importantly, why? What secrets do the Eleusinian Ministries hide, and what does the internet guru Jazz Phoenix have to do with EM’s Los Angeles Parthenon?

There on the back cover are my enthusiastic thoughts about what Jeff has achieved with the Doc Brazen series. I’ve been a Doc Savage fan for over fifty years, and have seen adaptations, pastiches, updates…but as I say on the back of Net Prophet, this series is head and shoulders above any previous effort to bring the pure pulp spirit of the original canon forward into a modern setting.

In more depth, here is what I said in the Introduction to the first Brazen book:

Ulysses Brazen Lives!

It takes a certain audacity to create a pastiche of an iconic literary character, and the world of authors does not lack for audacity. But in the cold light of critical assessment, combined with the loyalty (and stubbornness) of the original character’s readership, most fall far short. Why, after all, should a reader be attracted to a pastiche, when a wealth of the original character’s stories are available? Mostly, I think, out of a desire to experience the seductive joy that was felt in the reading of those original stories, but through the freshness of a current author’s perspective. Authors and readers come together in a unique symbiosis…and there is an excitement that comes when an old literary love is taken up by a contemporary writer who clearly shares that love.

But the road ahead from there, unfortunately, has seen that special form of audacity crash and burn far more often than it soars.

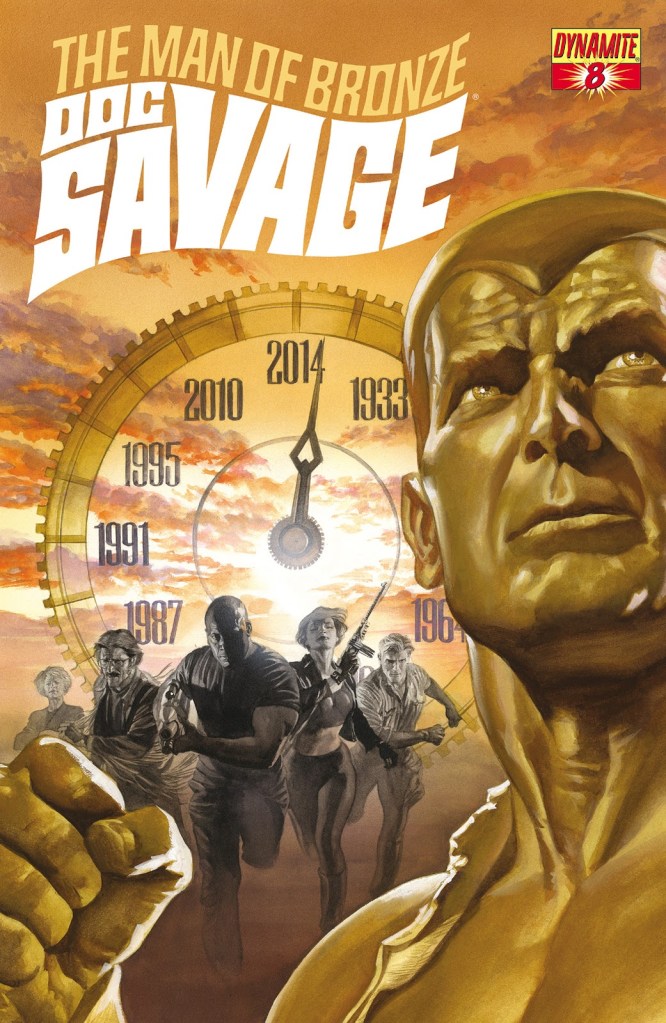

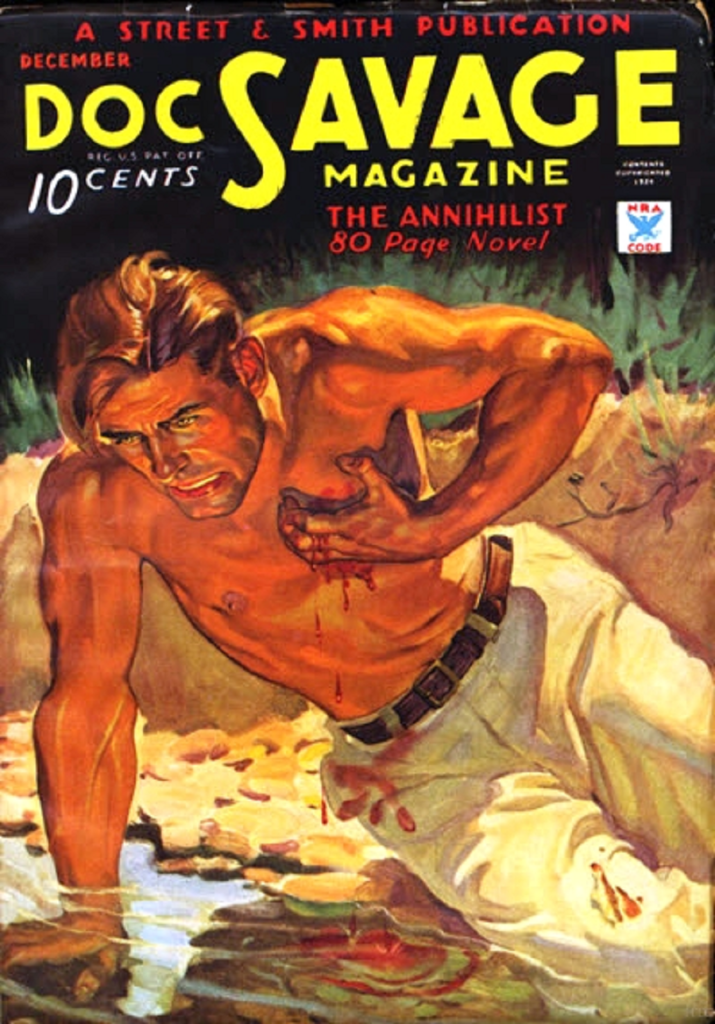

The source here is the character Doc Savage, arguably one of the most popular characters of the 20th century, and certainly in the era of the pulp magazines of the Great Depression, a giant of popular culture. The Doc Savage magazine ran for 181 issues, from 1933 to 1949, and inspired countless imitators, but it embodied a unique set of qualities that was beyond imitation. It took the qualities of its time – largely the privations of the Depression – and responded with storytelling that included agency (Doc kept many businesses afloat by investing in silent partnerships) and compassion (he was always ready to assist the common man, accepting no fees for his services). Into the mix went the escape of high adventure and globe-trotting exoticism. Never was a character more perfectly suited for his milieu.

Amazingly, those qualities resonated with a mass audience again in the 1960’s, when Bantam Books began its long series of paperback reprints. A phenomenon once again, Doc became a cherished hero for a whole new generation.

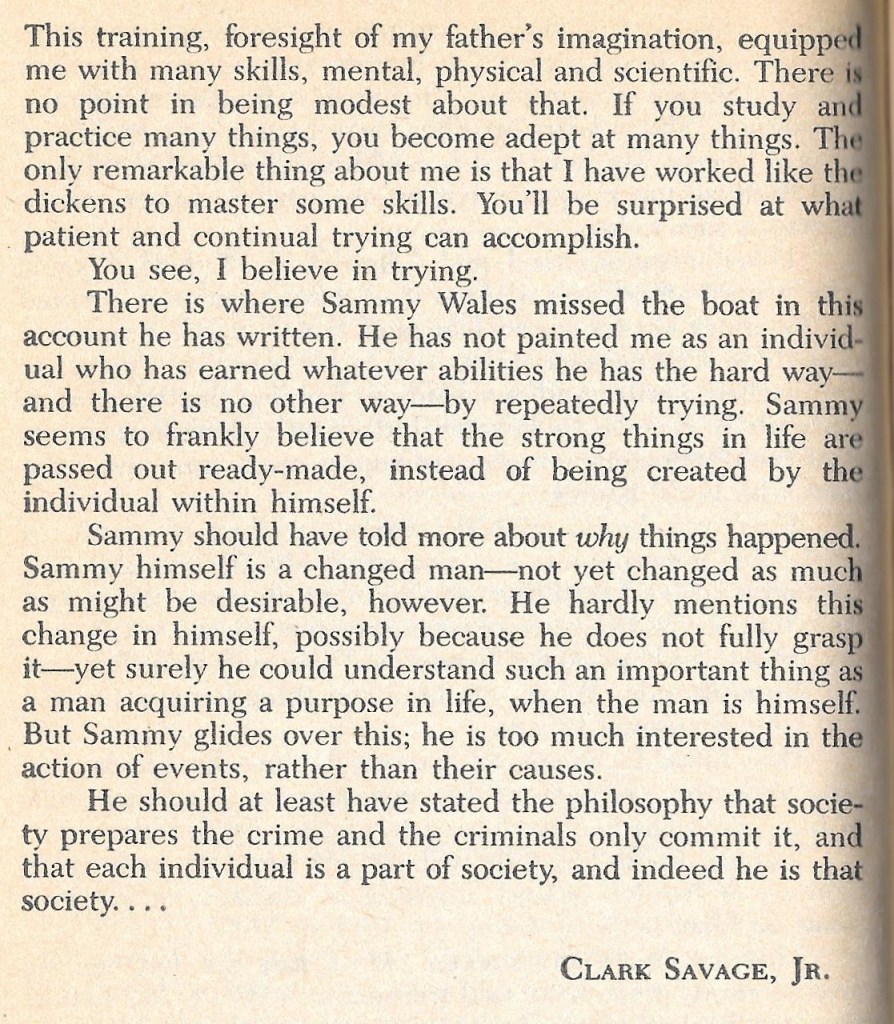

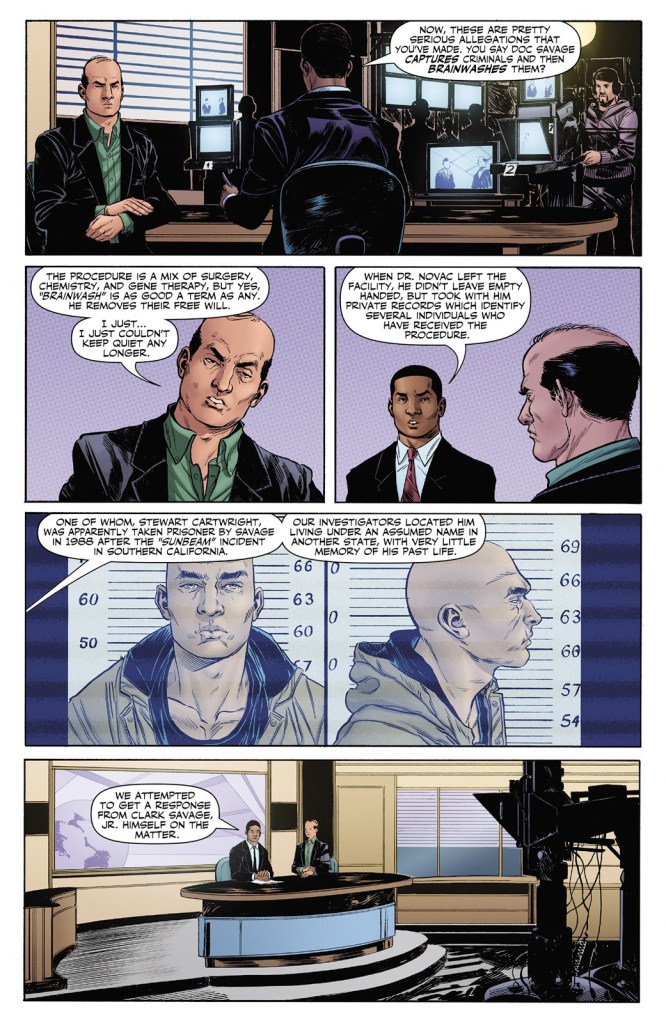

Since then, publishers and authors have attempted to recapture that lightning in a bottle. Through licensing of new novels, through comic books, through film. Some have been disasters, others have been earnest – and modest – successes. And then there has been pastiche. Characters (many of them named Doc), instantly recognizable as doppelgangers of the original Man of Bronze, have appeared over and over again. Some have been interesting, others workmanlike, but to my mind none captured the special alchemy of their source.

Until Doc Brazen.

The weakness of most of these pastiches, to my mind, has been rooted in a failure to grasp the complexity of the original’s appeal. They have seized on a single aspect of the character that seemed a key to success. Nostalgia (setting the pastiche character in the 30’s and drenching the storytelling in a kind of backward-looking glow), or adventure (keying on the somewhat sanitized violence of the pulps, often a strange mix of visceral danger and innocence), or simply repetition (attempting to copy the writing and plotting of Lester Dent or the other Kenneth Robeson ghosts and simply changing all the character names).

Such efforts, at their best, could be fun, but were hitting on only one cylinder of an engine designed for an immensely more powerful performance.

Even before discovering Jeff Deischer’s Doc Brazen stories, I was aware of his unique fascination with Doc Savage. His book, The Adventures of the Man of Bronze: A Definitive Chronology, had been on my bookshelf since 2012, and I had read it with great pleasure. The book’s dedication, “For Lester Dent, one of the great storytellers”, spoke eloquently of where he perceived the greatest strengths of the long history of the Doc Savage pulp magazine to be. So I was more than casually interested when I discovered, in 2018, that he had created his own pastiche of Doc. Upon seeking it out, it became immediately apparent to me that this was a unique take on breathing new life into a whole pulp mythos.

Visual design has always been a significant part of the Doc Savage mystique, and modern creators have stood on the shoulders of images by talents like Walter Baumhofer (pulp cover artist) and James Bama (paperback cover artist) for decades. But Jeff’s Doc Brazen #1: Millennium Bug took an innovative approach, tapping into the zeitgeist of 21st century symbolism, which uses simple, clean imagery and bold colors to carry its message.

Beyond that dynamic packaging, the book’s blurb described Doc Brazen as “the world’s most famous crimefighter, scientist and adventurer from the Thirties and Forties, coming out of his fifty-year retirement”. So this was not going to be another in the crowded field of stories mimicking 1930’s style and shoehorned into a canon already filled with a huge existing continuity of novels and novellas. This was a continuation into the present era, orchestrated by one of the character’s most accomplished researcher/chronologists.

Others have tried this (most persistently in comic book adaptations), and have immediately gone astray, primarily due to lack of a coherent vision. Doc stories brought forward into the latter part of the 20th century or into the 21st have felt like an uneasy graft of the past onto the present. Without exception, those efforts were short-lived. I had pretty much come to the conclusion, as a reader, that it couldn’t be done.

Nevertheless, I could not resist trying Deischer’s Doc Brazen. And as I read that first novel, I came to realize that it could be done…because it was happening right before my eyes.

Where other pastiches had been halting, limited in scope – or simply exercises in imitation – Jeff’s vision for a present-day Doc was richly layered, balancing with remarkable poise between respect for the original stories and the fresh energy of a present-day setting. Doc himself was plausibly brought forward in time, aging (his white hair actually providing him with a new level of dignity), but in such a way that he was hale and vigorous. His retirement after 1949 (to the small Central American country of Coronado) was explained, not through laborious exposition, but skillfully woven into a fast-paced action narrative. New, younger aides were introduced, with connections to the past that helped them feel familiar, but also refreshingly characterized with unique qualities of their own.

The story brought in elements of Doc canon – again, always in a plausible manner – which expanded, rather than repeated iconic concepts.

And most of all, hearkening back to the dedication to his Definitive Chronology, the storytelling captured the best of Lester Dent’s style while deftly transitioning it – removing anachronistic qualities, incorporating aspects of Dent’s quirkiness without ever descending into parody, and pacing the story in such a way that it remained exciting from cover to cover. It was superb craftsmanship melded to the intangibles that made pulp-reading so much fun.

For the first time outside of the canonical pulp stories, I felt completely caught up in the magic that had prompted me to fall in love with Doc’s stories over fifty years ago. Doc was alive again.

The question that remained was: could Jeff do it again? One of the great allures of the original pulps is the fact they comprise a continuing story. You are not done with one novel…there is another, and another, and cumulatively a whole world emerges that you can immerse yourself in. A kind of joy (well understood by the passionate readers of the world) enters your life when you have thoroughly enjoyed a book, and you can envision a line of them on your bookshelf that will continue the journey. Millennium Bug had a short blurb in bold text at the end, which read: Doc Brazen will return…

When the return happened, I absolutely intended to be there.

But time passed. 2019, 2020, and Doc Brazen did not return. There is a surface part of me that is a man in his sixties, who understands that the world – particularly the literary world – can be a place where dreams do not come true. But alive and well in me is the teenager who followed splendid continuing stories as if my life depended on it.

Time and circumstance, in this instance, was kind. Net Prophet is here, and much more is to come.

Reading the Brazen books has brought me back to days when I would await each Doc Savage paperback. My pulse would race when I spotted the new dynamic cover, and I could barely wait to get each one home and start reading.

So I am grateful. Jeff Deischer rekindled a joy that was sparked in me as a reader a half century ago. Doc Brazen is indeed alive, and in the best pulp tradition cast as a new vision for today, the world is better for it.

Check out these links to further explore the exciting world of the Doc Brazen series: