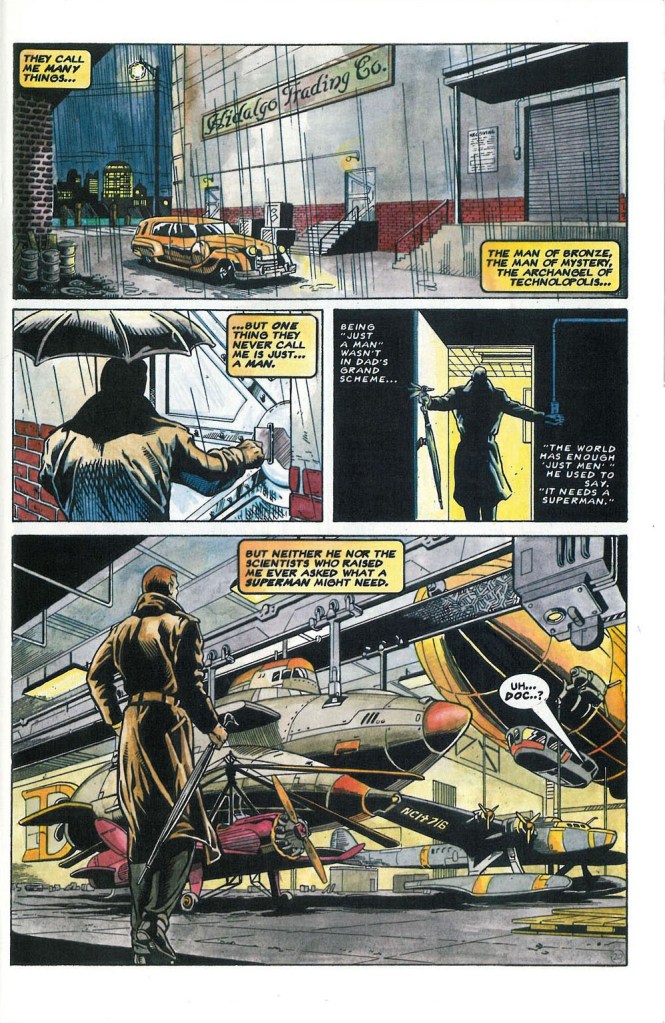

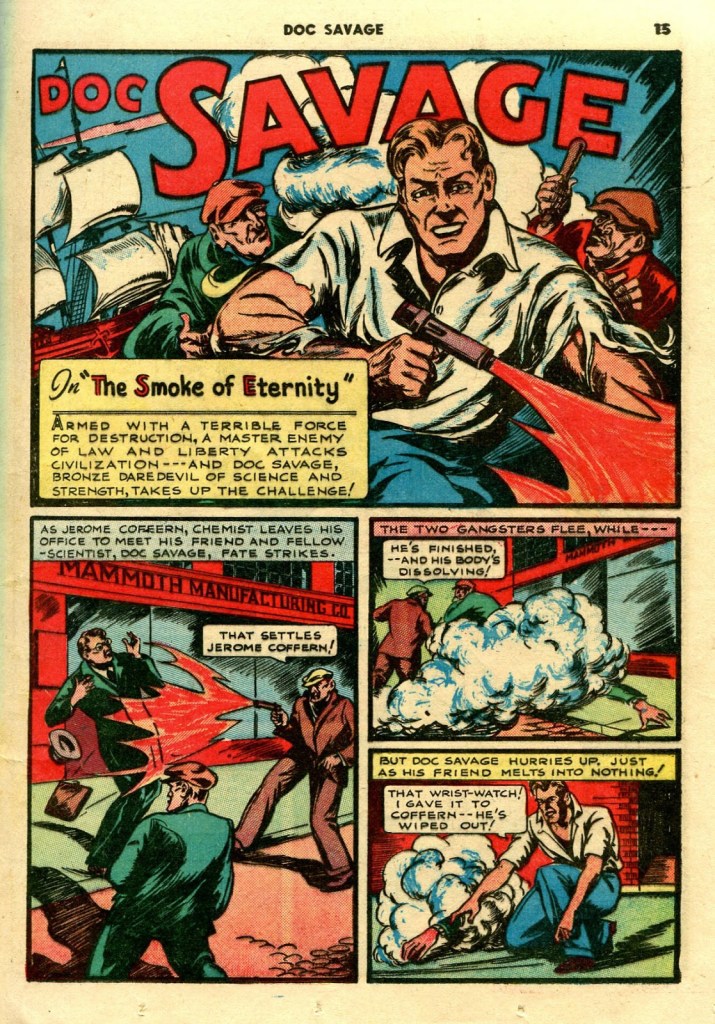

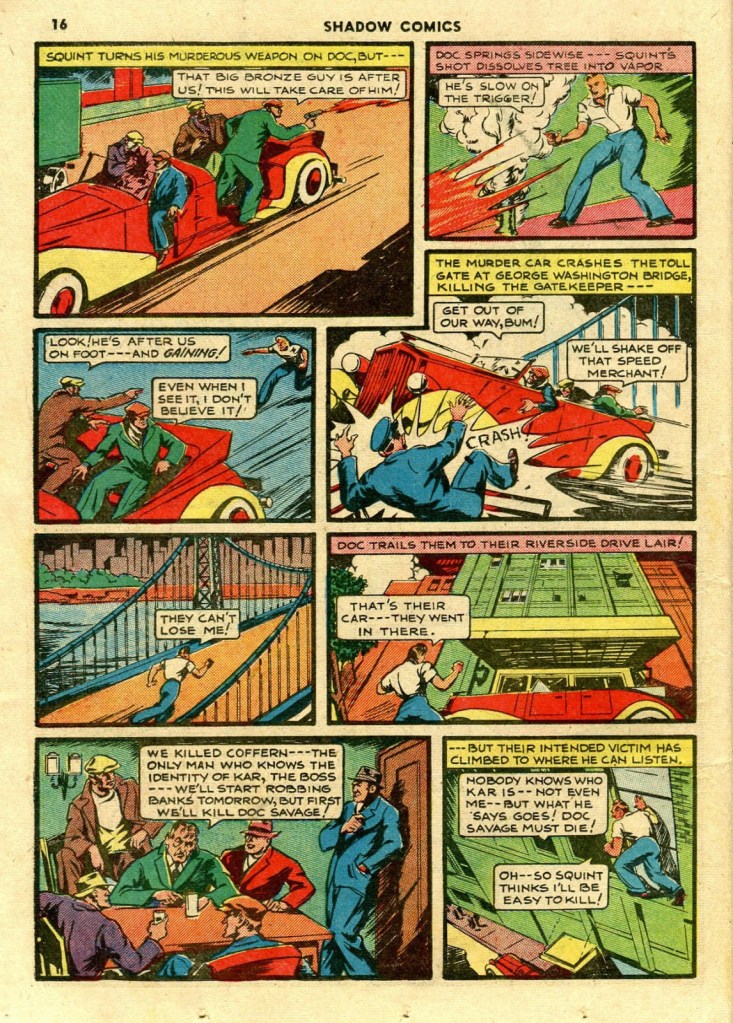

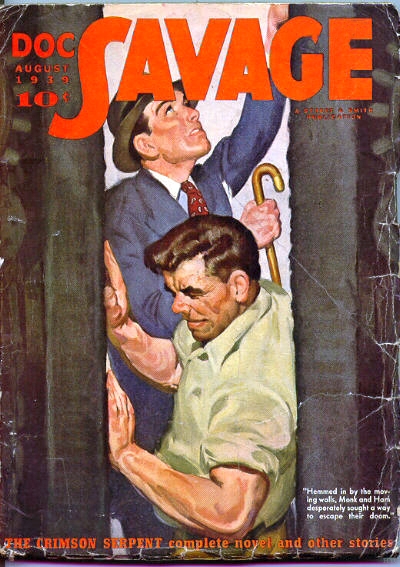

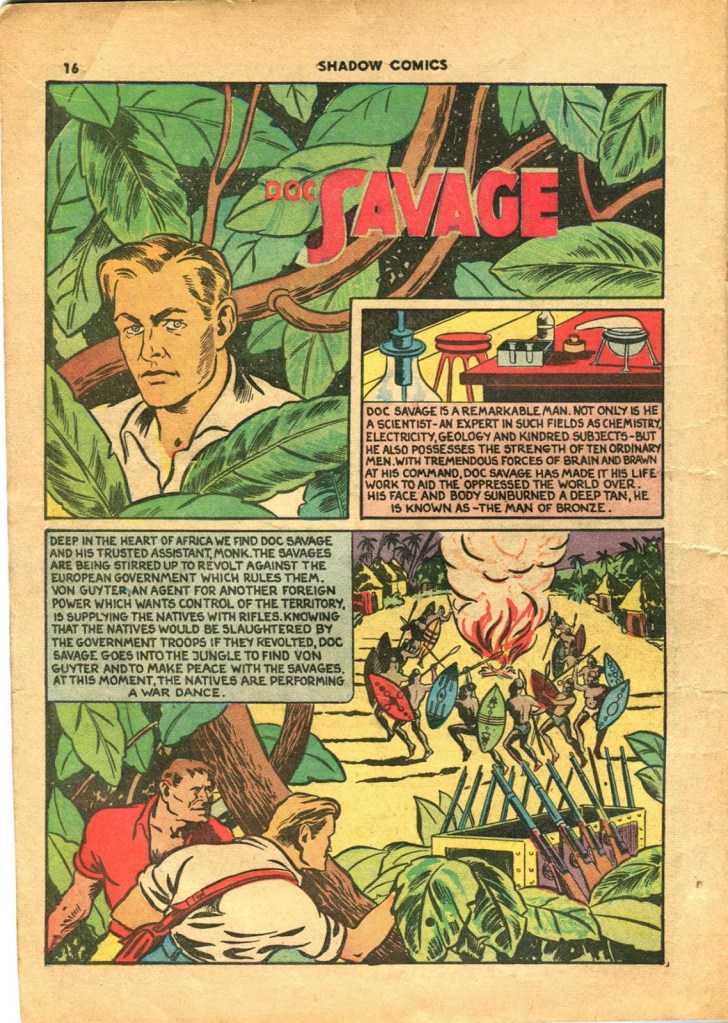

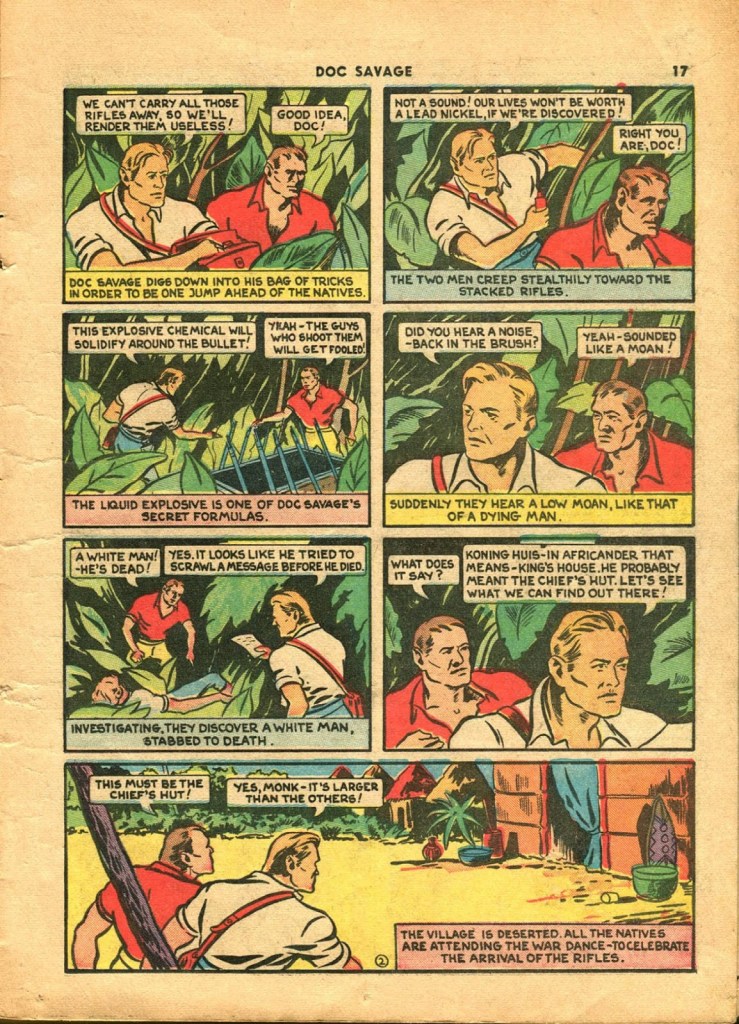

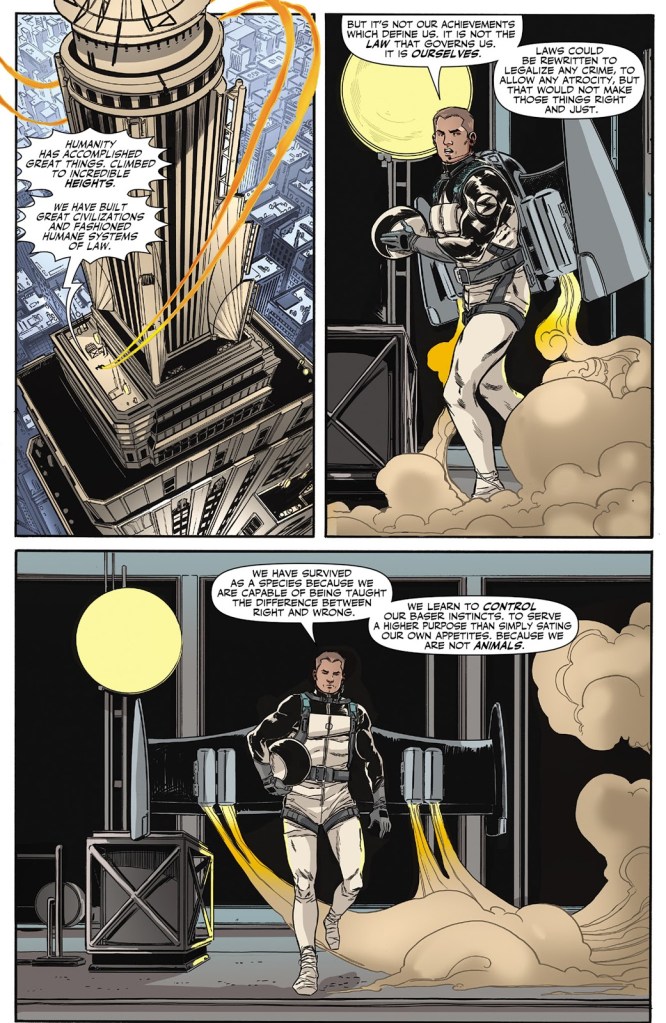

At the end of this article’s first segment, I suggested that the core of what the character Doc Caliban offered was a literary opportunity: to explore, using techniques of adult storytelling, a whole range of compelling human drives…from ethics and morality right down through atavistic behaviors of sexual hunger and need, and their link to human violence. I closed the article with a question:

Using Doc Caliban as a mirror with which to explore those themes, was that opportunity fulfilled?

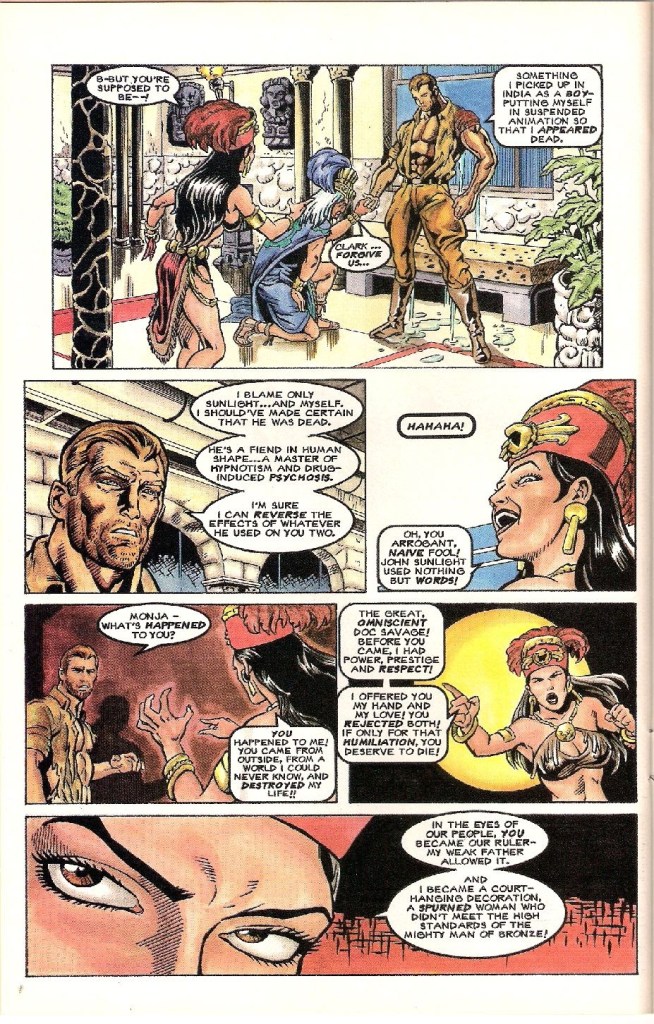

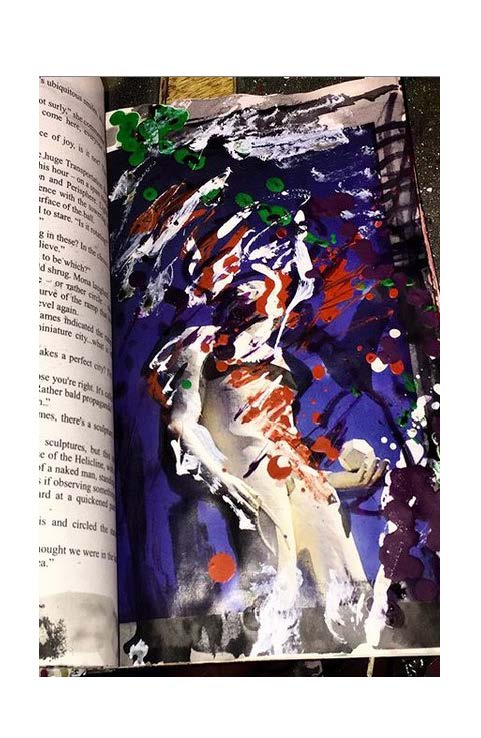

My feeling, unfortunately, is no. It was not. All of the elements to do so had been put into place, including iconic characters of primal cultural power (pastiches of Doc Savage and Tarzan), and a format — explicit adult storytelling — that opened the door to an extremely visceral experience. That door was opened and left beguilingly ajar at the end of A Feast Unknown, but then, bit by bit, nudged back shut.

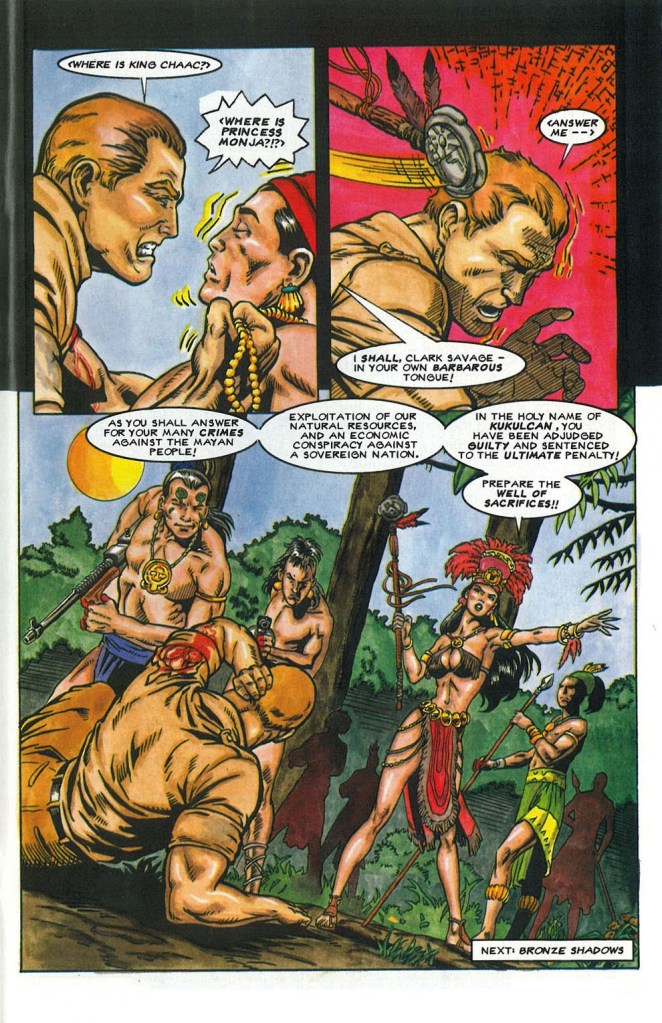

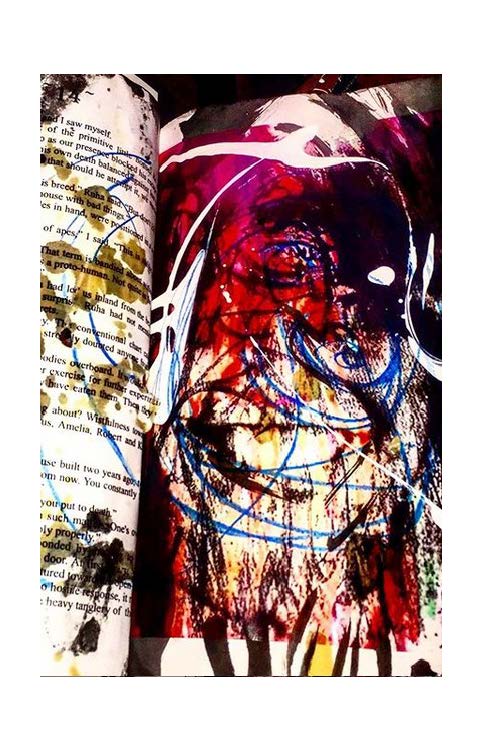

Here is where the issue of whether Doc Caliban was merely a parody or a character of depth in his own right becomes germane. As a figure of satire — an honorable man laid low by a form of sexual madness — his purpose for existing was essentially over at the end of Feast. None of the tantalizing depths in the question of how a reasoning — even noble — man could experience such a collapse of his beliefs are broached. Instead a deus ex machina was employed as a means to back away from those compelling themes. The state of insanity was induced by an external force (the Nine’s immortality elixir)…a resolution which makes for an easy escape from the depths of the Pandora’s Box that had been opened.

For a single potent satire — and Feast is unquestionably a powerful story — that adds up to “mission accomplished”. Though for me it left a sense of the unfinished in my mind as a reader…I very much wanted to see Caliban explored with a similar depth to that afforded Grandrith in the story. The themes were so compelling, and an “adult Doc Savage” was a remarkable potential means for looking deeper into that mirror of not only Doc, but ourselves.

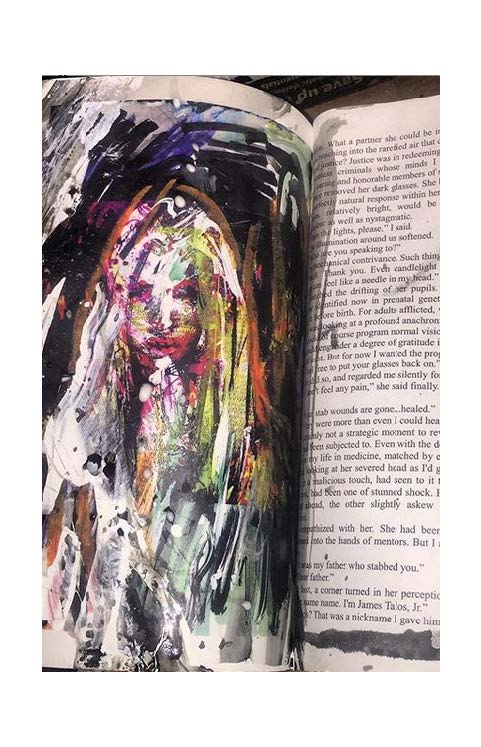

And the story did not end with the final scenes of A Feast Unknown, which included this last look at a Caliban physically broken by his brutal final conflict with Grandrith, but intriguingly, on the brink of opening a new chapter as a person. Here is that passage (the I of the narration is Grandrith):

…I tried to walk into Doc’s room, but the pain between my legs discouraged this. I allowed Clio to wheel me in beside his bed. He was lying there with a stiff plastic collar around his neck. Clio had done a professional job in doctoring his broken neck. He was flat on his back and staring up at the ceiling. Tears formed pools with a deep golden-green bottom in his eye sockets, and tears ran down his cheeks. Trish was crying also, but at the same time she was smiling.

“He hasn’t wept since he was a little child,” she said. “Not even when his mother died or his father died, did he weep. He must have an ocean down there, and I thought it would never come. Oh, I’m so happy.”

If he did not stop crying, she would not be so happy. He could be suffering a complete breakdown, or he could be on the road to a healthiness he never had.

I said, “Doctor Caliban, why are you crying?”

He did not answer. I waited a while and then repeated my question. After another long period of silence, he said, in a choked voice, “I am crying for Porky and Jocko and the other wonderful friends I had. I am crying for many people, for Trish especially, because she loves me and I gave her almost nothing back. And I am crying most of all, and I cannot help it, for me.”

This, more than all the rampant sex and violence of the narrative, is the kind of glimpse and beginning insight into a character that embodies adult writing.

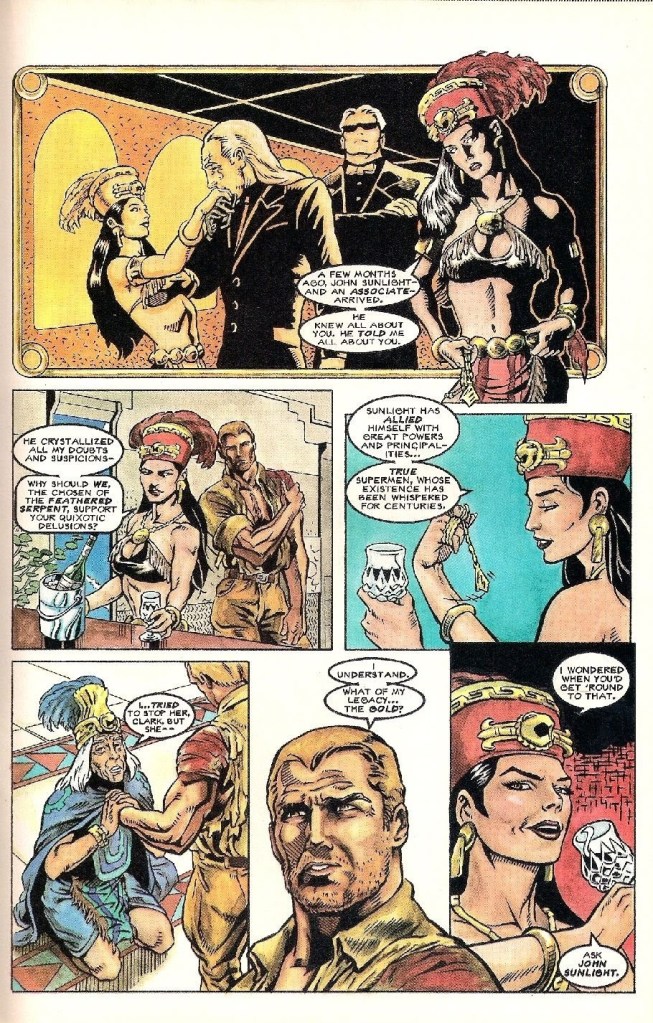

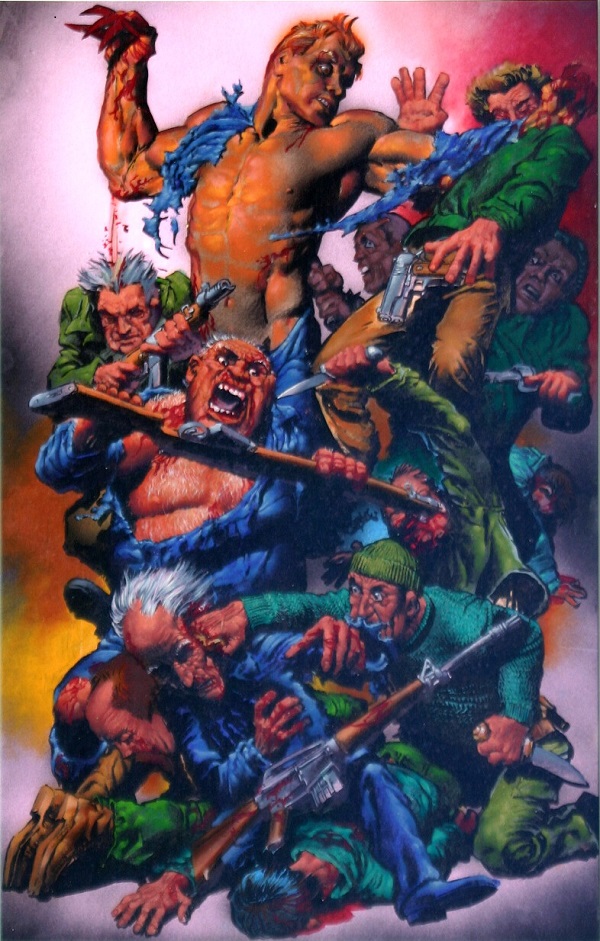

However, it was to remain only a glimpse. The book that followed did not even attempt such an ambitious alchemy of intense pulp storytelling wedded to powerful human drives and psychology. The double book The Mad Goblin/Lord of the Trees was an often clever and complex adventure thriller, but no more.

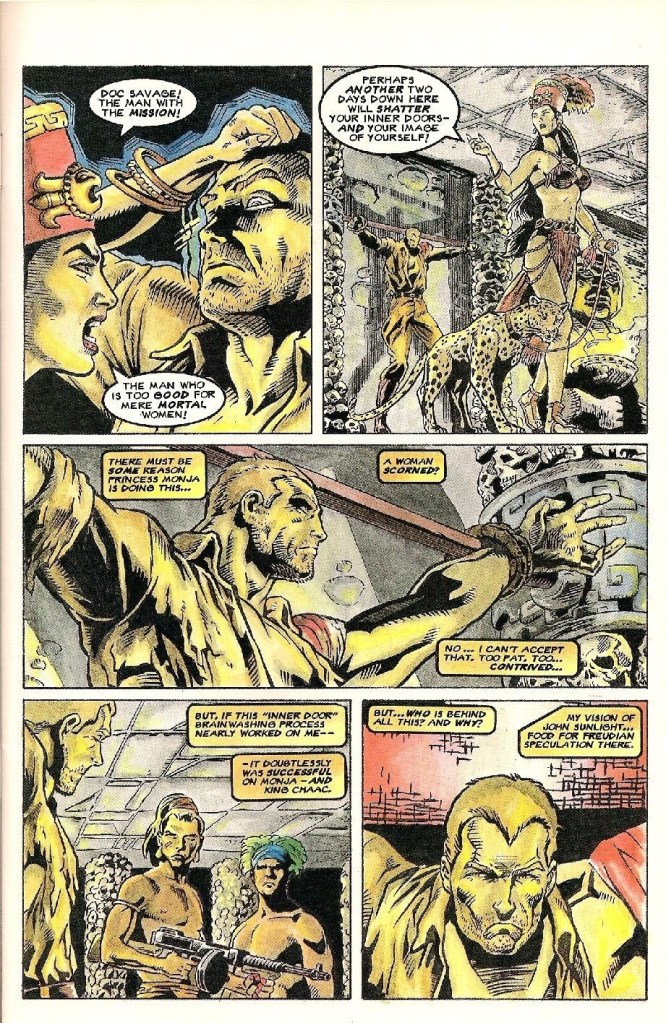

In his half of the book, the character of Doc Caliban had the potential opportunity to lay bare his own depths in the aftermath of the “insanity” that had turned him into a cruel, even an arguably evil man. But this is distinctly avoided. Farmer even employs the extraordinary device of an author’s note before the storyline of The Mad Goblin commences:

A Note from Philip José Farmer:

Although the editors of Ace Books insist on publishing this book as a novel under my by-line, it is really the work of James Caliban, M.D. Doc Caliban wrote this story in the third person singular, even though it is autobiographical. He feels that this approach enables him to be more objective. My opinion is that the use of the first person singular would make him feel very uncomfortable. Doc Caliban does not like to get personal, at least, he doesn’t like to do so with most people. Even the largest mountain throws a shadow.

Quite the disclaimer, and the narrative of the story remains true to it. Caliban, for all intents and purposes, is a non-character in his own book, going through a great deal of action, but little more.

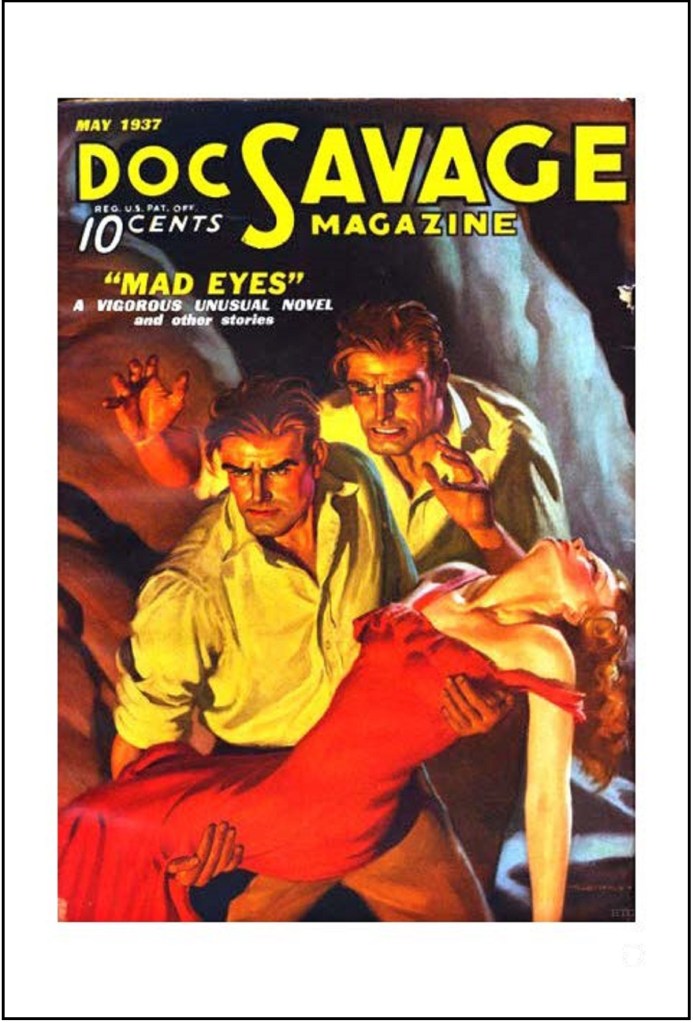

Farmer’s further plans for the character were equally vague. In the 1980’s he teased the premise for the book The Monster on Hold, essentially a continuation of the final Doc Savage pulp novel Up From Earth’s Center, done as something of a Lovecraftian mashup. The sample chapter he published appeared to have little of the tone from even The Mad Goblin/Lord of the Trees, and none at all of the series fountainhead, A Feast Unknown. (As noted in Part 1 of this article, the story has since been completed by Win Scott Eckert, and will appear later this year — which will be a review for another time.)

But I have little expectation that any core theme of Doc Caliban’s depths as a character will be attempted. At least I will certainly be surprised if the story assays to go there.

So as an adult mirror through which we, as readers, could look at some very intense, and certainly fascinating human issues, Caliban appears destined to be unfulfilled…the mirror of his deeper self splintered into fragments of genre play and wandering literary direction.